ARTS: ESSAYS, STORIES, IMAGES, & POEMS

SECTION EDITORS: ROBERT JOHNSON & BENJAMIN FEDER

Ball and Chain (Part 1)

by John Johnson

In prison, a person is a nobody. You’re bound, ball and chained, to an oppressive, degrading, merciless system that shows little regard for your well-being. Twenty-four hours a day, you’re subscribed to loneliness, accompanied by discrimination, racism, and a skimpy hot tray away from starvation. People don’t feel obligated to respect or recognize you. Neither of the two comes cheap. There is no privacy. You’re told when to wake, when to shower, how loud to talk, and when and where to eat.

A razor-wired electrical fenced gated community without immunity is what you see when you look out of your window. Inmates of all shapes and shades standing around wearing the same colors; no individuality or originality; just faded, stretched blue and orange threads. No one has it as hard as YOU. This is why it is called “hard time.” Away from your family, your children, your real friends, in exchange for pretentious associates (wolves in sheep’s clothing) and a stampede of racist pigs who come from home bringing in aggressive attitudes, covid, cold stares, and looking for reasons to make your incarcerated (already screwed-up) life an even hotter hell; enforcing hard protocols they don’t even follow. If you’re colored, you’re automatically inferior, and your matters don’t matter. I reckon it’s a hard pill to swallow.

New officers are nicknamed “green-tags” by the prisoners. Green is symbolic of new or fresh. Their first few days are understandably timid, but kind, catering, and very respectful. Oh, and not to mention, they actually do their job! However, it won’t be long before they have their hands full with cruel and unusual punishment and mental health negligence. The common courtesy they began with is eaten up by depreciative inmates who take over-advantage of any scent with an inviting hint, or they are moments away from being corrupted by more seasoned co-workers who impregnate their minds with seeds that give birth to the “correctional officer versus the prisoner” syndrome; telling the green-tags that prisoners aren’t to be trusted, and to oblige them accordingly. Now, all of a sudden, a green-tag is making it an issue to bring you a roll of tissue.

Mass incarceration, impoverished opportunities provided for you to rehabilitate, maced in your eyes, tased, punches, tossed around by guards, then thrown into cold, unsanitized cells flat on your face. Feces spread and smeared all over the place, all over the walls — from the mentally ill who cry out for assistance. Multitudes of prisoners are up next for parole, but bound by the system’s unyielding ball and chain. Clear evidence of excellent behavior. You’ve gone the full distance without violating any administrative rules, completed the required programs and passed classes with flying colors, but evidently, the government number on your back means more than your government name.

There are hundreds of thousands who actually share your pain. This is the psychological-reverse! that is designed to fold and break you, bird-feed your brain with hopelessness so you’ll revert back to miscreant ways. The “no way out” mentality. A “damned if I do, damned if I don’t” consciousness. The system’s master, its puppets, and the long list of plays. The manipulations that keep the prison business booming and afloat, keeping all its staff employed, at the expense of you being the joke.

John Johnson is originally from Detroit, Michigan, and currently resides in Baraga Correctional Facility in the Upper Peninsula. He writes poetry, essays, short stories, and film scripts. He is particularly interested in sharing the stories of those who suffer, both in and out of prison. Contact him at katbodrie@gmail.com.

Poems by Gregory “Royal” Fann

Poems by Anna Gephart

Who is the system?

It’s the system

It’s the system

It’s the system

They say.

We have to fix the system.

But the system didn’t do it on its own.

It’s the people

It’s the people

It’s the people.

We have to change the people.

Their minds

Their hearts.

It’s the people who made the system,

But who made the people?

Fear, anger, order

Made the people.

We have to fix the people

To fix the system.

Who am I?

Who am I?

I am a student.

I am a sister.

I am a daughter.

I am lucky.

I am seen and supported by everyone around me.

But not everyone is like me.

So many people

Are students

Sisters

Daughters

But are not labeled this way.

They are labeled ‘criminal’

Therefore unseen and unsupported.

Because once you are that,

We don’t like to think of you as anything else.

Social Butterfly to Cocoon

We are social creatures.

We need social interaction.

We depend on each other.

We don’t want to feel lonely or forgotten.

So what do we do to people who are incarcerated?

Deprive them of their wings.

Wrap them deep into the cocoon.

Who cares if they need social time, who cares if it’s inhumane?

They do the crime, they do the time.

But what entails the ‘time’?

When do we begin to commit the crime?

Poems by Samual Palos Kraemer

Murmuration

A murmuration of birds

A black eye, a split lip

A respite of sunlight

A homie from Hoover

on the way back from court

back to our cage

where dreams go to die

Hat Trick

He said I can do this too and did a backflip

I wonder what the other trick was

I didn’t know you had candy he said

as he slipped him a piece

smile ten yards wide as he looked at his hands

Sermon on the mount at metal octagon tables

Shahada in yellow shirts

It’s beautiful in here if you pay attention

Look twice you might miss it

Longevity

I pour my optimist glass half full

into my pessimist bowl of punch

and make a soup of sorrow

I jump off the boat of the future

into the sea of antiquity

in my time-traveling trousers

I attack the paper with my pencil

and hope to leave some lines unleashed

Samuel "Palos" Kraemer is a former heroin addict and gang member from Eastside Claremont. He just finished serving a year and a half sentence in Men's Central Jail, L.A. County. A new poet, he has published poetry in Street Sheet, and is working on his first chapbook.

My Fourth Day

By Lauren Greenberg

As I pull into the parking lot at seven AM, uncertainty about the day ahead washes over me. It is Thursday, June 27th, and it is my fourth day as a correctional officer atGrey Penitentiary. I step out of my car and into the ninety-degree heat with the harsh sun overshadowing almost everything. I took this position because it was one of the few available in my rural town. It pays well even though I didn’t go to college, and fulfills my hopes to serve my community.

During the first three days of my new job, I attempted to learn an entirely new world where the norms I knew went to the wayside. These men have spent years of their lives on death row, divorced from the outside world, and the prison environment reflects that isolation. I slowly get out of my car and walk toward the door, hesitating before stepping into the lobby. I knew today would be a learning curve not unlike the last few days, but I was far from prepared for what awaited me.

I went about my routine, shadowing Officer Jackson who has been here for years.We walk toward the chow hall; we are supervising breakfast this morning. Within the first few minutes of arriving, I hear yelling across the room.Two men are fighting over the same seat at a table. The men scream in each other's faces so they can sit where they are most comfortable. They begin pushing each other– Officer Jackson breaks up the fight before further violence erupts, but he seems unfazed. It seems he has become accustomed to the violence, the suicide, and the devastation. He says this happens often, but today tensions are high because a member of the community is being put to death at midnight. Before taking a job at the prison, I knew this was what I signed up for, but death just four days into the job wasn’t in the description.

It’s time for count. I make my way toward the cells, hoping everything will go smoothly. I walk by each room, ensuring everyone is present and everything is in order.Each day I’ve been curious about the space the men spend most of their time in. As a trainee, I’m only a voyeur. I’m not allowed to spend too much time peering into the hundred or so little quarters existing within the prison walls. But I look anyway– at the sparse photos on the wall, the bare necessities, and the barren conditions.I know the new guy shouldn’t speak up, but I ask Officer Jackson why the prisoners cannot have more personal items if they are here for so long. Why, if they spend so many years existing within these concrete walls, should it not feel like home? Bluntly,

he says “what’s the point? They’re on death row. Anyway it keeps us safe” The other officers with blank stares nodded, confirming his sentiment. I am unsure whether they are unempathetic or whether they have become accustomed to the environment, forgetting that these are humans forced to live here. Of course I don’t tell them this, I respond that it makes sense. After all, I think I’m here for the same reason they are– to protect my community and make sure victims receive justice.

As I approach the recreation yard, I am startled by the somber mood. Concrete walls, concrete floor. It’s not a yard because there’s no sunlight, no grass. I thought the inmates would be working out or playing a game, but they are still as statues. OfficerJackson tells me most days are different, but death days are usually like this. He says that on normal days segregated groups stand apart, but today feels oddly communal. Everyone seems to congregate around one person, and I wonder if it is he who will be put to death tonight. My thoughts are confirmed when a tear rolls down his cheek as friends, not knowing whether they’ll speak to him again, express their last loving sentiments. I know days like these are more somber, but I never thought about the toll an awaiting execution takes on the entire community, seeing friends of ten, twenty or thirty years shipped to the death chamber.

Hours pass. The rest of the day is an uneventful blur. I am too focused on midnight. Officer Jackson tells me that as part of my training he can take me to the execution. After witnessing the general toll of the awaiting death, a voice in my head tells me not to go, but I drown it out. This is what I signed up for. Maybe seeing the victim’s family and their hurt will outweigh what I’ve seen today. After all, he is a murderer, right?

I make my way to meet Officer Jackson outside the death chamber, and we step inside the cold, sterile room. Only the execution team is here, and I cannot see into the gallery. The curtains are drawn as if we are preparing for the opening act of a sadistic play. The air smells stale and of chemicals you would find in a doctor’s office. I try to count my breaths, anxiously waiting for the prisoner to be brought in. I ask the team his name– Benjamin Holmes, they say. So I am anticipating Benjamin to be brought in.

Officer Jackson says he is taken to the chamber while other inmates sleep to prevent any further commotion. He likely spends his last conversations across from his lawyer or loved ones, but there’s no touching allowed until their goodbye. Officer Jackson tells me he will be brought to the deathwatch chamber with a spiritual advisor until the execution team is ready. I’m not sure I believe in God or an afterlife, but I know I would seek answers in my last moments, pondering where my soul might end up.

Benjamin is brought into the chamber. He doesn't look at me, but his eyes are filled with despair. The executioners guide him to the table as if they have done it a

thousand times before. In an attempt to absolve them of full responsibility, each officer takes charge of a different limb. They strap down the left leg, the right leg, the left arm, and the right arm. They puncture each of his arms with an IV as if he was an animal ready to be put down. I cannot help but think about how procedural it is, step by step, ensuring the routine runs smoothly. At this point, Benjamin is just flesh to them. I’m not sure I can see him that way.

The curtains to the witness room have been closed, probably to shield viewers from the gruesome reality of lethal injection, but the officers begin to open them. I first see who I believe to be the victims’ family. They look content but somber, gazing down at their laps with their hands intertwined. I can tell they are seeking closure and justice–something, anything to ease their suffering. I then lock eyes with Benjamin's family. I can feel their pain, their eyes searing a hole into the glass that separates them from their son, sibling, and grandson just to get one last look at Benjamin alive. I witness a precious moment between Benjamin and his loved ones as he cranes his neck toward their seats in an effort to say,

“I love you.”

The clock strikes midnight, and within minutes he is injected with the death-inducing drugs. I see his family, a cascade of tears streaming down their faces. I become overwhelmed by the ending of my fourth day at work. Benjamin is not just flesh on the table; he is not just a murderer; he was a human being with people who loved him.I wonder if this is what justice looks like– inflicting more harm on a family who, just as the victim’s family, will be in pain for the rest of their lives having lost a loved one. The victim’s family suffered a loss, but now Benjamin’s family is suffering too.

I pack up my things and quickly head outside. In the pouring rain, the water steams as it hits the hot pavement. With my coat over my head I rush to the car, fall into the driver's seat, and sit in pure silence. My brain fills with thoughts I wish I could push away. I came here to serve and protect. I came here to do something worthwhile for my community. The court documents, prosecutors, and judge would say Benjamin is a bad person, a criminal deserving of his fate. Four days ago I would have said that too. After seeing the human toll of execution, I am not sure it’s that simple anymore.

Lifer

By Phillip Vance Smith, II

lifer

the correctional officer says

good morning

i ask

what’s so good about it

she replies

you’re alive

humph

why is life such a good thing

they say

waking up

is a gift

but they’ve never

been awakened

to the sound

of men screaming

as homemade knives

pierce bellies and necks

because they used

the blood’s phone

or didn’t pay the crips rent

or called an aryan brother

a bitch

before breakfast

they say

waking up

is a gift

but they’ve never

been awakened

three times

during the night

for headcounts

with a flashlight

beaming in their eyes

to verify

that their sorry ass

is still

alive

they say

life is a precious gift

i ask

a gift of what

living in prison

waiting to die

because that’s

the only way

i’ll see the outside

they say

life is a gift

humph

prison

makes me wish

someone would

take it back

lifer

Phillip Vance Smith, II is editor of the longest-running prison periodical in North Carolina, The Nash News. His essays have appeared in The Humanist and The Spring Hope Enterprise. He is co-author of the Prison Resources Repurposing Act, which intends to give people with life without parole sentences a second chance through a stringent education- and work-based program. Smith has been serving life without parole for murder in North Carolina for twenty years

Leo Cardez is an award-winning inmate writer. Cardez is a Pushcart Press Prize and Best American Essays-nominated essayist and journalist. Mr. Cardez is a winner of the prestigious PEN America Award and was published in a print anthology earlier this year: Prison Blues. His work has been or is scheduled to be published in The Evening Review, The Harbinger (NYU Review of Law and Social Change), and Spotlight on Recovery magazine, Under the Sun online zine, The Abolitionist/Critical Resistance newspaper, The Crime Report online publication, Minutes Before Six online zine, Prison Journalism Project, Beat Within, Fortune News, Breakthrough Magazine among others. He was a finalist for the New Press anthology, What We Know. Leo is a regular contributor to Prison Health News where he also serves on the Advisory Board. L.C. has worked as a prison GED tutor, COVID-19 quarantine wing sanitation specialist, and currently works as a clerk at the prison eye lab. He volunteers as a yoga instructor for special needs inmates and translator for Spanish-speaking offenders. Mr. Cardez is a proud first-generation Hispanic, decorated veteran, devout Christian, and is passionate about using his voice to bring awareness of criminal justice and mental health/addiction issues. He can be reached at Leo.Cardez.Writer@gmail.com.

What to the Lifer is Prison Reform? [1]

By Phillip Vance Smith, II

The abolitionist Frederick Douglass once asked the United States of America, “What to the slave is the Fourth of July?” Douglass’ question juxtaposed the Fourth of July with American freedom and forced listeners to examine what freedom meant to those living in bondage. During Douglass’ time, one could only conclude that American freedom meant nothing to the slave because they were not free.

In this modern age, I ask: What to the lifer is prison reform? I ask this because the standard story of prison reform compels shorter sentences for nonviolent offenders as a means to reduce mass incarceration. On the other hand, it demands lengthy sentences for violent criminals because they committed crimes causing harm to a victim. The standard story denies the fact that most state prisoners are violent offenders, and if they remain in prison, mass incarceration can never be reduced. Ignoring this truth prevents the standard story from accomplishing its own goal. By solely focusing on a person’s unchangeable past, society loses sight of the changeable future an incarcerated individual could have, if given the opportunity. Criminal justice reform should not only focus on releasing prisoners; it should center on building better citizens in preparation of release.

How can reducing lengthy sentences for violent criminals serve society better than only reducing sentences for nonviolent criminals? Success relies on method. By redirecting the current trend of warehousing people — to building better human beings through goal-oriented programs — the carceral system can lessen prison violence and release mature citizens without posing the threat of violent recidivism.

A Solution to the Problem of Mass Incarceration

My name is Phillip Vance Smith, II. I was convicted of murder twenty years ago, and I am serving life without parole. I entered the system almost a decade after mandatory minimum sentencing laws took effect. This tough-on-crime phenomenon eliminated parole, higher education in most prisons, and all incentives to live virtuously. Over time, I watched North Carolina prisons deteriorate from a scholastic oasis to an educational desert overrun with violent gangs, drug addicts, and others who demonstrate no growth in maturity. Combine this void of education with a system lacking meaningful opportunities to earn release, and prisoners serving an array of sentences have no incentive to value personal change. Such an environment prevents progress instead of promoting it.

In 2020, I coauthored a legislative proposal with Timothy Wayne Johnson entitled the Prison Resources Repurposing Act (PRRA), which aims to accomplish two main goals: to reduce prison violence and to address mass incarceration in North Carolina. [2] To accomplish these goals, the PRRA gives hope to hopeless prisoners by securing release for exceptional lifers willing to earn it through stringent requirements. [3] Without incentives like early release to work toward, long-term prisoners prioritize survival. Most prisoners lack stable support systems when they enter institutions, and prison jobs pay insufficient wages, so survival in this context usually means participating in illegal activities to gain financial stability. Because long-term prisoners are more settled into the system, their mindset of survival through nefarious means controls prison culture by preying on impressionable prisoners seeking guidance. Many from that impressionable group return to society with a nothing-to-lose mentality. Long-term, violent prisoners determine whether those released return to society as better citizens or worse criminals.

The framework of the PRRA offers parole to lifers after twenty years’ incarceration once they complete a fifteen-year plan mandating educational and occupational goals to help refocus the negative mindset of surviving in prison to the meritorious goal of succeeding after release. To accomplish the requirements of the PRRA, the potential parolee must first remain infraction-free for a period of five years. Afterward, the North Carolina Post-Release Supervision and Parole Commission will review the potential parolee’s behavioral record and decide if the candidate should be enrolled in the program. If accepted, the potential parolee must obtain a GED if they do not already have one. Next, they must complete at least one vocational trade program. Lastly, they must work in the North Carolina Correction Enterprises or a commensurate incentive wage occupation. Once the fifteen-year plan is completed, the potential parolee may be paroled for five years after serving twenty years in prison, totaling the time under supervision at twenty-five years.

To take the PRRA a step further, Timothy and I created the PRRA Phase II, which can apply the same stringent requirements to non-life sentences — or, more specifically, long-term consecutive sentences — to allow early release. [4] Consecutive sentences, or virtual life sentences (50+ years), act as life sentences because a person serving one will most likely die in prison. By applying the PRRA to consecutive sentences, all long-term prisoners can benefit from a system of merit-based parole. Furthermore, the North Carolina prison system will benefit from a reduction in prison violence because those same long-term prisoners who once lived nefarious lives with no chance for release will now work toward obtainable goals through hard work and maturation. The PRRA Phase II can be applied to any non-life sentence by assigning the length of the requirements’ phase at 50% of the total sentence, and capping time served at 65%. [5]

North Carolina legislators found merit in our proposal. Eighteen Democratic House Representatives co-sponsored the PRRA in 2021 after it was drafted as HB 697. Unfortunately, the PRRA died in committee for that particular session, but lawmakers promise to sponsor it again in the near future, signaling a dedication to changing how North Carolina punishes violent crime. [6]

Why Merit-Based Parole is Important to Society

To reduce mass incarceration, lawmakers must not only focus on releasing nonviolent offenders; they must find ways to refocus priorities of violent prisoners and reshape their influence on others. Those goals can only be fulfilled by pairing incentive with development — the incentive of release for long-term prisoners, by way of their development through the accomplishment of goals to achieve personal growth. Without release as a goal, long-term prisoners have no motivation to change, creating a negative environment from which worse criminals may be released back into society.

Some will oppose releasing violent offenders; specifically, murderers. Historically, American courts have employed mandatory sentences, such as LWOP, to those found guilty of murder in order to deter crime. [7] The logic follows that public viewing of heinous punishments prevents criminals from committing felonies that could become murder. Professor Daniel S. Nagin of Carnegie Mellon University argues against such logic: “There is little evidence that increases in the length of already long prison sentences yield general deterrent effects that are sufficiently large to justify their social and economic costs.” [8]

In 2022, NPR reported a 35% rise in gun violence since 2019. [9] If LWOP sentences prevent crime, why the recent rise in murder rates? As Professor Nagin found, lengthy sentences do not deter crime. Murder and gun violence rise because lawmakers refuse to address the root causes of violence, such as poverty, disparities in mental health treatment, and racial injustice.

Recent trends in rising gun violence should have no bearing on whether people who have been convicted of a violent crime should be considered fit or unfit for release. Despite polarizing headlines, murderers are released every day. A person can serve fifteen years for second-degree murder as the result of a plea deal and be released without earning an education, working, or making any positive life changes. [10] How is this possible? Because mandatory minimum sentencing laws eliminated early release incentives as goals. In contrast, by offering early release to long-term prisoners through mandated educational and vocational goals, society will benefit from a released prisoner’s personal growth and development.

In reflection, the question should not be: What to the lifer is prison reform? Perhaps we should ask ourselves: What can prison reform be for the lifer?

References:

[1] Portions of this work are derived from an article previously published in the North Carolina Law Review. See Phillip V. Smith II & Timothy W. Johnson, “Hope for the Hopeless: The Prison Resources Repurposing Act,” 100 N.C. L. REV. 713 (2022). https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol100/iss3/2/

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] “The felony murder rule was promulgated to deter even accidental killings from occurring during the commission of a dangerous felony.” State v. Richardson, 462 N.C. S.E.2d 492 (1995)

[8] Daniel S. Nagin. 2013. “Deterrence in the Twenty-First Century.” Crime and Justice 42, no. 1, 201. https://doi.org/10.1086/670398.

[9] Becky Sullivan and Nell Greenfield-Boyce. “Firearm-Related Homicide Rate Skyrockets Amid Stresses of the Pandemic, the CDC Says.” NPR News, 10 May 2022, NPR.org.

[10] Id.

Phillip Vance Smith, II attends the College at Southeastern as a junior and works as a Writing Consultant in the North Carolina Field Minister Program. His essays have appeared in The Humanist and The Spring Hope Enterprise. Smith sits as editor of the longest running prison periodical in North Carolina, The Nash News. He has been serving life without parole for murder in North Carolina for twenty years.

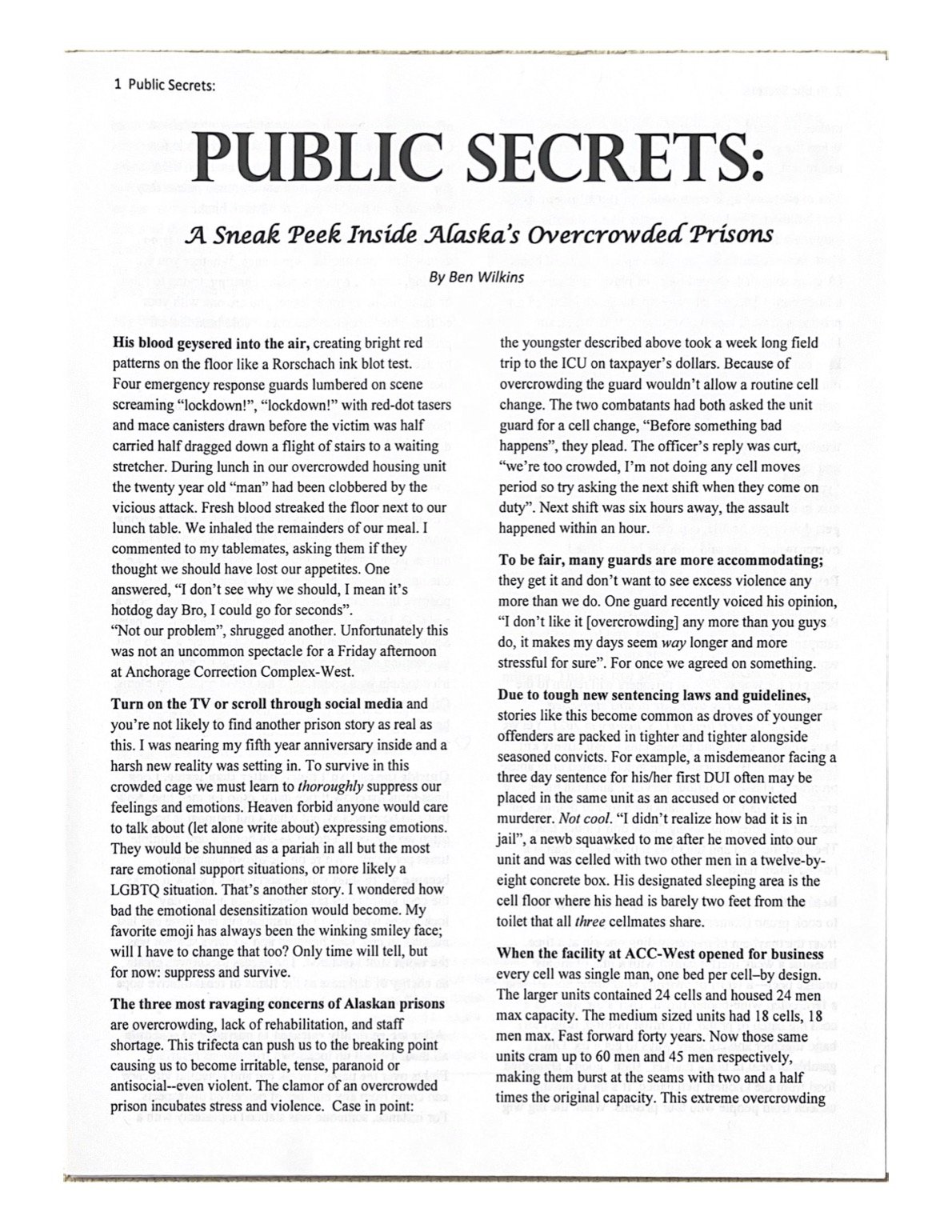

Ben Wilkins is a contributing writer for Spotlight on Recovery Magazine and the National Buddhist Newsletter. His work has been published with The American Prison Writing Archive, Minutes Before Six, and elsewhere. Though currently imprisoned in Alaska, he believes life is only 10% what happens to you and 90% how you respond to it. He hopes to inspire others thru writing. He is hungry for opportunity, feedback, and gladly accepts correspondence @ the address listed.

Gender Translation

By Britney Gulley

Who am I?

A paraphrase of life. Misconstruing the physical with an altered thought. Conveying a message that cannot be decoded or deciphered.

A transcript of style. Explaining how, or why, who is removing the significance that convered growth and the world. Lifeless change is interpreted.

A simplification of spirit,

A Transformation of soul,

A metamorphosis of existence;

All these rephrase mortality. Redndering self-essence an illusion. A version of behavior simplified in transfiguration.

Who am I? Transparency of a vital flame that through expression has been improving, although unconscious.

Gender Translation.

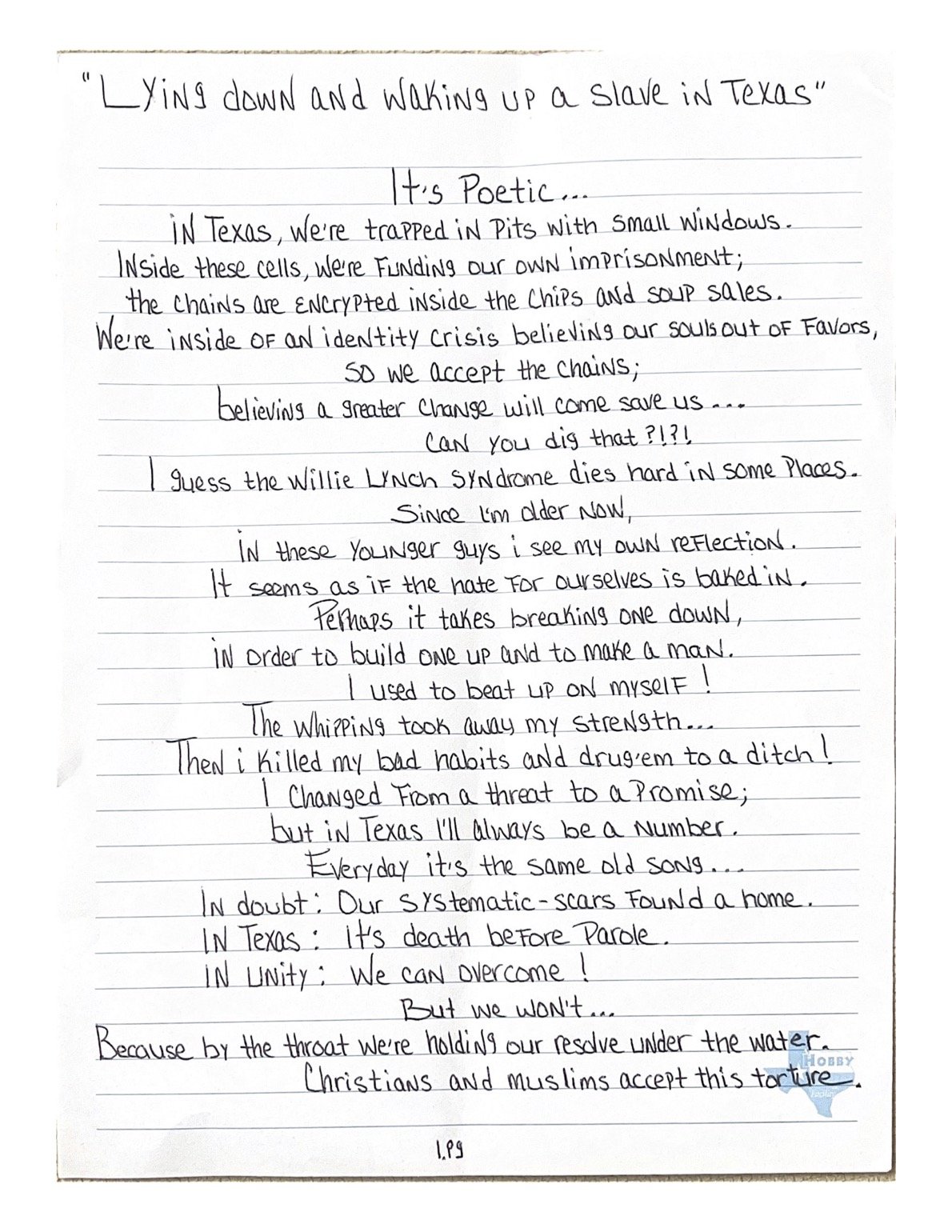

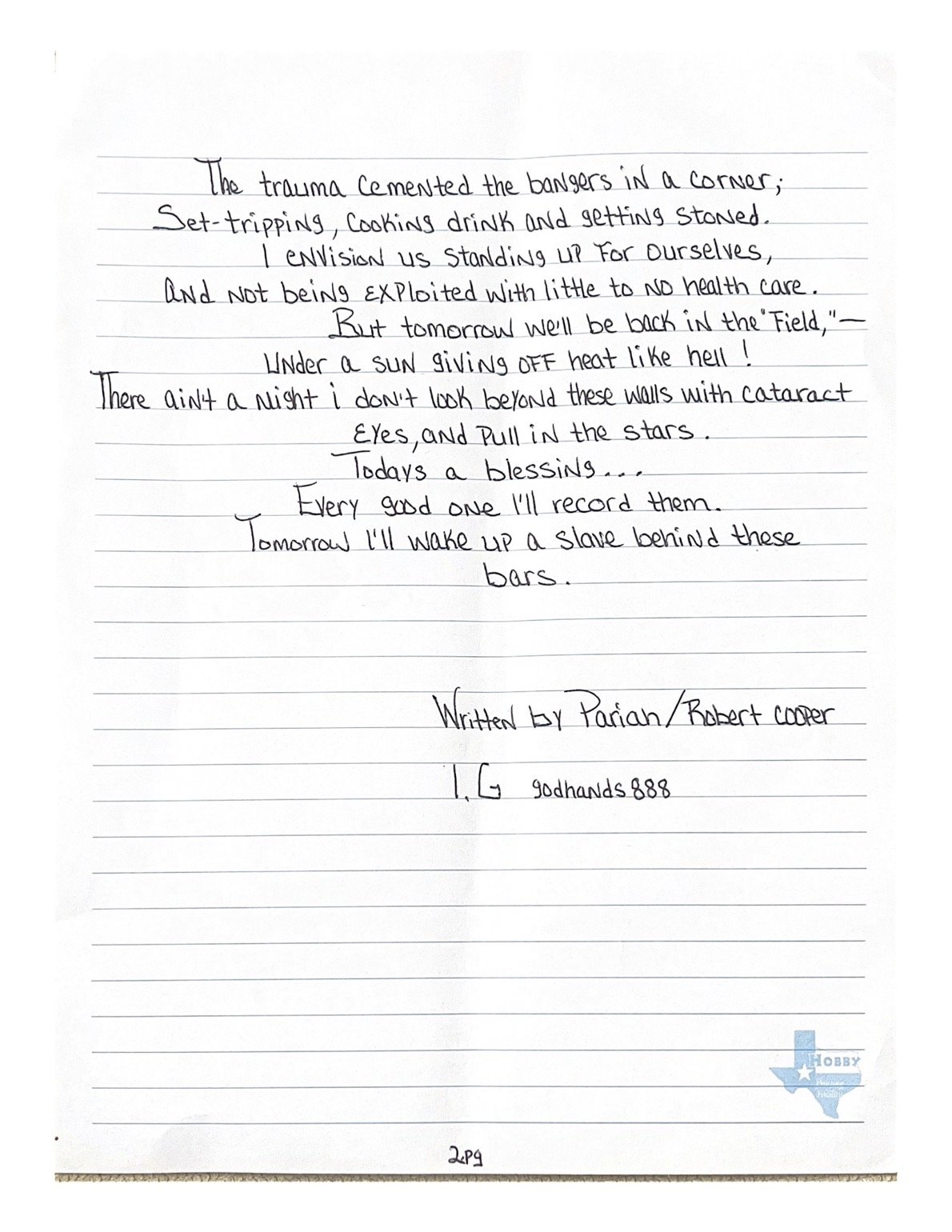

“Lying Down and Waking Up a Slave in Texas”

By Robert Cooper/ Pariah

Deconstruction and Dehumanization: An Examination of Prison Spaces Through Art

By Carly Johnson

What do you think of when I say the word “specter,” or “haunting”? Maybe you think about Halloween, ghost stories, horror movies. The association is there, certainly, but I want to challenge you to think about something else.

Hi, my name is Carly Johnson. I am a student at American University where I study philosophy and politics. In the course of my studies, I enrolled in a class called “the prison community,” taught by Professor Robert Johnson, where I have been challenged to reframe my understanding of prisons and the people held within their walls in the United States. The class focuses on the lived experience of incarceration, and we were encouraged to develop creative projects, such as the one you’re listening to right now.

Living Without You

By Rev. Cari Willis

The moments leading up to your execution were filled to overflowing with anxiety and love. We had one ear focused on soaking up every last word we spoke to each other. And the other ear was doggedly straining to hear the hushed voices of the correctional officers behind us as we awaited them saying our time was up and you needed to make your way into the death chamber. When those words were spoken, we smiled at each other with tears puddling in our eyes. We held each other’s hands through the slot in the cell as we professed our undying love for one another. No last hug. No embrace that let you know how I loved you with every fiber of my being. Just tearful smiles. Just love.

And then they killed you.

And no one told me what it would be like to live without you. No one told me that I would cry almost every day. No one told me how waves of grief would sneak up on me at the worst of moments. No one told me that there would be a silence to my grief that would shout, time and time again, that it needed to be heard. No one told me that the pain in my heart would be so unbelievably profound. No one told me that the grief would never end.

I guess I was expected to just move on with my life. But I can’t. I won’t. You were the most unique friend I have ever had. You loved me with a massive love. You laughed and laughed loudly. You shared with me your entire self with such graceful vulnerability. You painted beautiful pictures of the unbounded love of God. You hugged me so tightly that after all these years, I can still feel your embrace. Our relationship was the purest one I have ever had: We just loved each other, we saw the best in each other, and we believed that God’s most magnificent gift was when God brought us together. And when we met, there were no prison walls. It was just us — almost as if we were suspended in time and place despite the clanging and banging all around us.

But now, I have to live without you. I want to remember just the love and not the trauma of watching you get killed. I want to hear the peals of laughter versus the last tears you cried. I want to recall every conversation we ever had, mining for all the goodness, love, and light, and not see instead the pain you endured. I want to pray with you, forgetting the fact that I could not say one last prayer over your dead body. But I can’t stop the trauma tapes from playing in my heart and in my mind. The tapes are on a continuous loop and have wound their way around my brain and my heart in an insidious fashion.

I now know more than ever that love never, ever ends. I know you are with me as much as the spirit world allows you to be. But I still have to live without you. I know you told me not to cry for you. But I cry just thinking of your request as I scream into the ether, “BUT YOU ARE NOT HERE!”

People who are against the death penalty will often say that more killing means more harm. I am a living testimony that the harm lives on and on and on. The harm and the grief will live with me until I no longer have breath.

No one told me what it would be like to live without you . . .

Reverend Cari Willis is a volunteer Chaplain to men who reside on death row in North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Florida, where she has found the most remarkable friendships.

The Life of One Death Row Chaplain

By Rev. Cari Willis

“In the place where he had learned to die, he had learned also to live.”[1]

I say there are three S’s to pastoral ministry: Show up, sit down, and stay silent. Over these seven years of sitting silent with those on the Row, I have learned so much about real living from them. As we have faced their looming deaths and their darkness, we have realized together what is most important in life. One of my friends recently wrote that 1 Corinthians 13:13 stopped him in his tracks: “And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love.” This is the summation of what I have learned from my beloved friends.

As I sit silent, I get to hear about their faith journey. The journey inevitably takes a long trek through the darkness. The first impulse is to turn the light on and try to make things “better.” But instead, I make the more painful decision to sit still in the dark with them no matter how dark it gets. The excruciating “WHY?” is asked over and over again. The relentless drumbeat of the harm caused to the victim's family screams loudly in their ears. They hypervigilantly replay the crime, wonder where God was during their horrific childhoods, lament over severed relationships. Tears are shared. And the darkness feels claustrophobic at times as the rehashing of thei life is exposed. And eventually, without fail, the light comes on. It may be the smallest flame, but the puzzle pieces that have been strewn across their faith path come into view. Neither of us has the puzzle top, but this is where their faith will have them clinging to a God who thankfully has the puzzle top and sees how their life will come together more beautifully than they could ever hope for or imagine.

As I sit silent, I hear about the hopeless feelings. I hear about unjust justice systems. I hear about hope that feels dangerous to feel, especially as my innocent friends hope for their freedom one day. And the hope strand may be the tiniest one ever, but we both grab hold with all of our strength and believe that somehow — some way — life will be different. The end of their story hasn’t been written yet. Hope can be found in the most unlikely of places.

As I sit silent, I hear how love has woven its way into their lives through the surprising love of penpals and family members who have vowed to stick with them no matter what. Love climbs into their dark cells and weaves its magic around their broken hearts. It calls them “beloved” again and again. It refuses to leave. It transforms their hearts and minds and gives them back their dignity and humanity. I repeat the words often and with tenderness: “I love you.” “You know what? I love you.” They know these are not just words from their spiritual caregiver, but are words from God too.

As I sit silent, I am a witness to the power of faith, hope, and love. Watching how these can radically transform a life has been an overwhelming joy for me. The way through the wilderness can be a wild and treacherous feeling at times. But I have learned to just sit silent — to sit still — and to watch the magic of faith, hope, and love.

[1] Belden C. Lane, Solace of Fierce Landscapes Exploring Desert and Mountain Spirituality, (New York, Oxford University Press, 2014), 171.

Reverend Cari Willis is a volunteer Chaplain to men who reside on death row in North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Florida, where she has found the most remarkable friendships.

WAITING

By Killian Lozach

Masum

Justin

Boy

ACT I

A dark prison cell.

One dimmed fluorescent light fixed to the ceiling.

A bed.

Evening.

Masum is sitting on the floor of the cell wearing his prison blues. His tray of food is next to him as he tries to force himself to eat but repeatedly spits it out. He gives up.

Enter Justin.

Masum: Nothing to eat. Nothing to do.

Justin: I feel the same way. All my life I’ve had nothing to do. I don’t know if we can even call this a life.

Masum: (Stands up.) You’re back? I haven’t seen you in forever. I thought you were gone.

Justin: I’m glad to see you too, Masum.

Masum: Well this is cause for celebration! Come here and give me a hug Justin.

Justin: Not now Masum.

Masum: When then?! You disappear and you won’t even tell me what you’re doing here.

Justin: Same as you.

Masum: Waiting for Ramiel?

Justin: Ramiel. Yes, he did say to wait here, right?

Masum: Yes, in this cell with the light fixture. (Pause.) Do you know of any other cells like this one?

Justin: I’m not sure. But there’s no one here. (He looks around.) And what if he doesn’t show? What do we do then?

Masum: Then I guess we’ll wait till tomorrow. Hope springs eternal, they say.

Justin: Does it? Sobering. And then the day after tomorrow?

Masum: We’ll come back.

Justin: You’re relentless.

Masum: We came here yesterday.

Justin: Ah (Pause.) No, you’re wrong.

Masum: Well then, what did we do yesterday?

Justin: (He repeats sarcastically) What did we do yesterday?

Masum: Yes.

Justin: What…(Angrily.) I still think you’re mistaken.

Masum: I’m almost certain.

Justin: Do you recognize this place?

Masum: Well. (Pause.) No.

Justin: Then how can you be certain we were here yesterday.

Masum: It makes no difference. It’s all pointless.

Justin: You sure it was this evening?

Masum: What?

Justin: For him to come?

Masum: (Confused.) For who to come?

Justin: (Angrily.) Ramiel of course

Masum: Oh yes. (Pause.) He said Thursday I think.

Justin: You think?

Masum: If we’re here we must be correct. We just have to wait for him.

Justin: But you said you were here yesterday. If you were so certain then, then why would he show up today?

Masum: (Agitated.) Can we please stop talking for a minute? I need some rest.

Justin: (Softly.) Alright. (Masum lays back down and closes his eyes. Justin paces around the cell, stopping and gazing every once in a while.) Masum! Wake up! Did you hear that? (Masum slowly opens his eyes.) I think I heard something. It must be Ramiel.

Masum: (Stands up, listens, then looks around confused.) I don’t hear anything.

Justin: I’m getting tired of waiting. What if he never comes? What if we’re waiting for nothing?

Masum: Let’s wait a little longer. I’m curious about what he has to say.

Justin: And what did we ask him again?

Masum: Were you not there?

Justin: I must have been, otherwise how would I have known to come here. I must have not been listening attentively.

Masum: Nothing very definite. A sort of prayer.

Justin: Precisely.

Masum: A supplication.

Justin: And what did he reply?

Masum: That he would wait and see.

Justin: That he would have to think it over.

Masum: Consult his friends.

Justin: His family.

Masum: His books.

Justin: His bank account.

Masum: His lawyer.

Justin: Makes sense.

Masum: Seems like the normal procedure.

Justin: I think so.

Masum: I think so too.

Justin: Oh look there! (The door to the cell opens. A blinding light shines into the room.)

Enters a boy

Boy: (Timidly, shy.) Masum…

Masum: Yes, that's me. Speak up boy. Approach.

Justin: What is it?

Boy: Ramiel

Masum: Obviously… Do you have a message?

Boy: Yes.

Justin: Well, what’s the message?

Masum: (Violently) Will you shut up Justin. Let him speak.

Justin: I want to know what kept him so late.

Masum: Who cares if he was late, he’s here now and he has a message. (The boy grows afraid.)

Boy: I’ve been here for a long time. It’s not my fault sir.

Justin: I don’t care anymore. Just give me the message.

Boy: Ramiel won’t be able to make it this evening. But he will surely be here tomorrow. (Pause.) And I will too.

Masum: Is that all?

Boy: Yes sir.

Justin: And you work for Ramiel?

Boy: Yes sir.

Masum: And what do you do for him?

Boy: I wait. (Pause.) I deliver messages.

Justin: Of course. And you said you will be here tomorrow?

Boy: Yes. And the day after.

Masum: Why is that?

Boy: Same as you. Waiting for Ramiel

Justin: Ah I see. (Pause.) We all have hope.

Masum: All right. You may leave now.

Boy: What should I tell Ramiel sir?

Justin: Tell him you saw us.

Boy: Yes sir.

Masum: You did see us...(pause.) Correct?

Boy: Yes sir. (The boy turns back and runs out the exit. The cell door behind him shuts.)

Masum: Well what the hell are we supposed to do now?

Justin: I don’t know… but I’m tired of waiting for this Ramiel. Who does he think he is?

Masum: Yes you’re right. Screw him.

Justin: We should stop waiting for him. Let’s just leave.

Masum: How? We’ve tried this before and we always end up here.

Justin: (Looks around for a couple of seconds until he sees the hanging light above and stops.) What if we hang ourselves?

Masum: Why?

Justin: Why not?

Masum: Good point. We’ve waited long enough.

Justin: What does it matter?

Masum: How? That matters.

(Justin looks around a little more. He sees the bedsheet.)

Justin: That! (He points at the bedsheets.)

Masum: You think that could hold us?

Justin: Why don’t we try?

Masum: Wait. (Pause.) How do we hang both ourselves?

Justin: Don’t worry. You go first and then I’ll go. It’ll work… trust me.

Masum: If you say so. (Justin ties the bed sheet onto the light and then fashions a noose to place around Masum’s head.)

Justin: Alright. Now you put this around your head and drop. Should be easy.

Masum: Goodbye. For now.

Justin: For now?

Masum: What does it matter? We wait.

Justin: Ah, waiting. That’s what we do.

Masum: True.

Justin: One way or the other.

Masum: Trust me.

Masum’s body drops and sways for a little while. The bedsheet held. His breathing stops. Motionless. Time passes. The cell door opens. First a yell, then an alarm goes off. Guards come running in. They surround the body of Masum, hanging from the light fixture above. No one else is in the cell. Hope may spring eternal, but justice? Not in this life.

Killian Lozach is a first-year undergraduate student at American University studying International Relations and Philosophy. He is currently a part of the Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps where he hopes to commission as a second lieutenant after graduation. Although his passion for public service has led to the path he is on today, Killian finds himself absorbed in the world of creative writing and poetry.

Special Topics

Section Editors: Robert Johnson and Benjamin Feder

A Preliminary Case Study about the Psychological Effects of the Death Penalty

By Lyle C. May

Investigative Reporter

September 2022

As an investigative journalist, I conducted an informal survey of the prisoners in my living unit (Unit Three) on North Carolina’s congregate death row. This survey was conducted solely on my own initiative during the month of November 2021. This survey examines my peers’ direct lived experience on a congregate death row under a sentence of death; it is not abstract imaginings of some legal theory or policy. As such, the survey is important because it makes an argument of fact, not just law, that offers new evidence about life on a congregate death row to lend weight to understandings of life under sentence of death, which I contend is a violation of the Eight Amendment.

One should think of this survey as a kind an affidavit from me and my peers. For this reason, and because I wanted to give voice to the plight of my peers, I carried out the survey to the best of my abilities, promising anonymity to respondents and, further, promising that I would do my best to get the results of the survey published. As a matter of investigatory ethics, I did not record names or keep a list of names of respondents. Nor did I link names to observations. There is no way the identities of individual respondents can be determined by outsiders. I, myself, cannot identify names in relation to observations since I recorded information by topic, not under individual names.

Forty-three persons were surveyed. There were no refusals. Fully 41 of the 43 have been on North Carolina’s death row at least 20 years or more and were present when executions occurred with regularity. That is, they lived daily, for years on end, under a prison regime that regularly carried out executions of their neighbors. The general sense among my fellow prisoners was that this was a chance to express their views on a vitally important topic—the lived experience of death row in an active death penalty state—views that, sadly, are ignored by the prison and the larger society.

Survey Questions:

1. Do you take any prescribed psychotropic medications such as an SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor), antidepressant, or antipsychotic?

For this question, some respondents required descriptions of the medication, the name of the medication, or how it made them feel to understand what they were being asked. 12 respondents acknowledged taking the anticonvulsant Teyretol, prescribed for an “off label” use as a psychiatric medication. 21 of 43respondents claimed to take some type of psychotropic medication and had not done so prior to incarceration.

2. Do you speak with a psychologist or psychiatrist?

21 of the 43 respondents claimed to have spoken with either a psychologist or a psychiatrist within a 30-day period.

3. Other than pretrial detainment, have you spent a year or more in disciplinary segregation?

18 of the 43 respondents claimed to have spent a year or more in solitary confinement while under a sentence of death. Of the seven who returned to solitary on multiple occasions, this was throughout the course of their confinement on death row. The 18 respondents were currently taking psych meds.

4. Do you currently experience any of the following: anxiety, panic attacks, fear of impending death, clinical depression, emotional flatness, apathy, lethargy, anger, rage, an inability to concentrate, memory lapses, paranoia, psychosis, suicidal ideation, schizophrenia, depersonalization, derealization, or hypersensitivity to light, sounds, or smells?

These symptoms were chosen because they have been listed as symptoms associated with death row “syndrome” and death row “phenomenon” by the European Court of Human Rights and other international courts. All respondents answered affirmatively to six or more of these symptoms.

5. On a scale of one to ten, with “1” representing low to none and “10” representing high to extreme, rate each of the previously listed symptoms.

All respondents measured moderate to extreme chronic depression, feelings of powerlessness, hopelessness, directionless anger, trouble concentrating, and hypersensitivity to light, sounds, and smells. Fewer experienced psychosis, schizophrenia, paranoia, and depersonalization/derealization, with only six respondents claiming a measure above “moderate” (5).

6. If you experience these symptoms and refuse treatment, can you explain why?

This question was the only one requiring a more involved answer. Not all respondents answered this question, but those who did gave four general answers for refusing treatment: 1) ineffective treatment; 2) the treatment would not alter the death sentence, which was the presumed cause of the symptoms; 3) the offer of medication was perceived as a “pacifier” or control mechanism that would make it easier for staff to manipulate the prisoner’s actions (this particular response was given by four prisoners who experienced heightened paranoia); 4) the psychological effects were part of the death sentence (this particular response was given by nine respondents and may be demonstrative of “catastrophic thinking,” an element of clinical depression).

7. Do you think your long-term confinement on death row is a form of psychological torture?

All respondents answered affirmatively, with four willing to drop their appeals if they could be executed immediately.

8. Have you ever been confined to the Mental Health Unit Six or been diagnosed with a severe mental illness such as bipolar disorder, dissociative identity disorder, major depression, or schizophrenia?

Two respondents claimed a diagnosis of schizophrenia, four respondents claimed a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, one respondent claimed a diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder, and one claimed to have been diagnosed with all of the above. It should be noted that I have witnessed these individuals in the social setting of North Carolina’s congregate death row. Each of these seven men has displayed symptoms related to their mental illnesses, each struggles to perform basic daily tasks such as eating and showering, and each is visibly dysfunctional in the social environment.

Lyle C. May is an investigative journalist, abolitionist, Ohio University alum and member of the Alpha Sigma Lambda Honor Society. While he pursues every legal avenue to overturn his wrongful conviction and death sentence, Lyle advocates for greater access to higher education in prison. His fight is that of millions and while the opposition is strong, his desire for equal justice is stronger. To read more of Lyle’s writing, visit ScalawagMagazine.org.

Editor Biographies

Robert Johnson is a professor of Justice, Law, and Society at American University and a widely published author of fiction and nonfiction dealing with crime and punishment. His short story, "The Practice of Killing," won the Wild Violet Fiction Contest in 2003. Several of his works have been adapted for the stage. His best known work of social science, Death Work: A Study of the Modern Execution Process, won the Outstanding Book Award of the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences.

Benjamin Feder is an honors graduate of American University, holding Bachelor of Arts and Master of Arts degrees in Art History with a focus on Humanism and the Italian Renaissance. His experiences as both an artist and a student of art history are what initially compelled him to start a career in the art industry. Benjamin has worked in museums and galleries in both New York City and Washington D.C, and is currently working at one of D.C’s top art advisory firms. As an artist, Benjamin works mainly in sculpture, creating works that interrogate the complex relationship between humankind and the environment.

Kat Bodrie is a professional writer and editor based in Winston-Salem, NC. Her editorial credits include Crimson Letters: Voices from Death Row (second edition), 1808: Greensboro’s Monthly, and Winston-Salem Monthly, for which she is a frequent contributor. Her poetry has appeared in North Meridian Review, Poetry South, West Texas Literary Review, and elsewhere. She is working on a poetry collection about spirituality, sexuality, and the aftermath of suicide. A former community college English instructor, tutor, and tutoring coordinator, Kat enjoys Pilates, correspondence with death row inmates, and a good glass of wine. Read her writing at katbodrie.com.