Table of contents

ARTS: Essays, Stories, Images, & Poems

Section Editors: Robert Johnson & Benjamin Feder

THE SHU

By Tiffany Gilligan

Solidified thoughts

By Tiffany Gilligan

Criminal justice class

By Tiffany Gilligan

Feeding on the hand

By Tiffany Gilligan

Solitary seasoning

By Tiffany Gilligan

Daughters of Thetis

By Chandra Bozelko

What happens at the intersection of race, disability, and the criminal justice system?

By Wrigley Kline

Why Did I Stop Him?

By Eliza Orlando-Milbauer

A WomAn in prison reflects on selective abuses of police authority

By Erin George

If the Kenosha shooting happened anywhere else in the world…

By Wrigley Kline

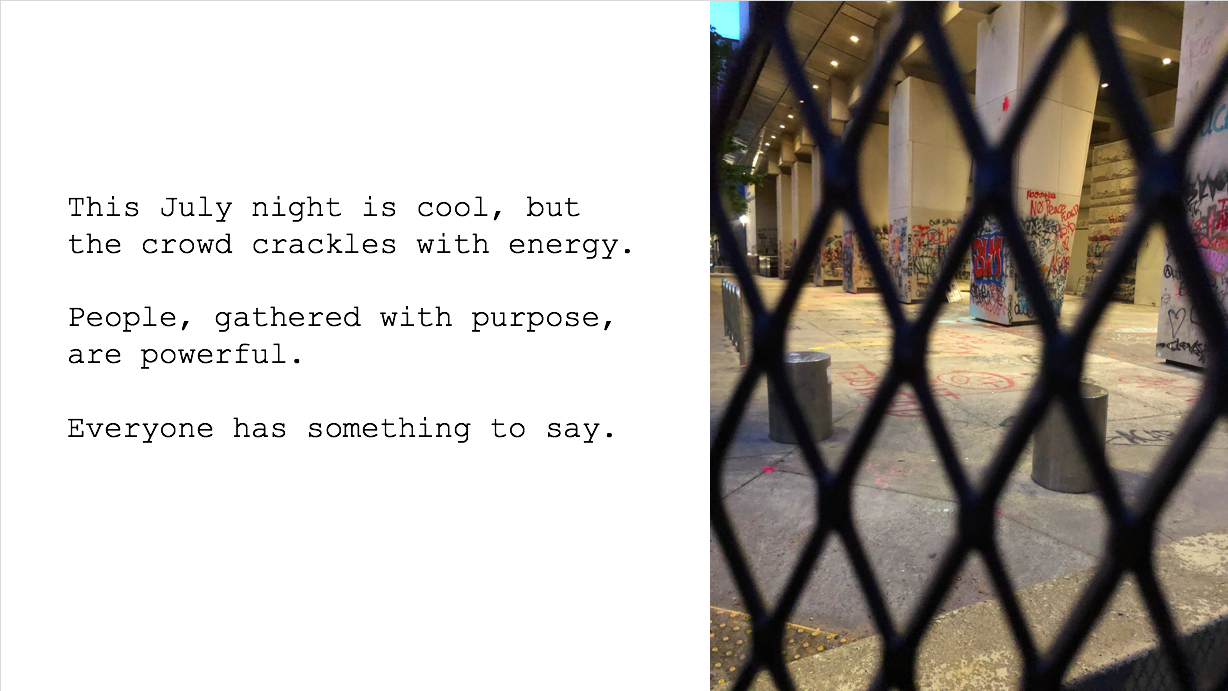

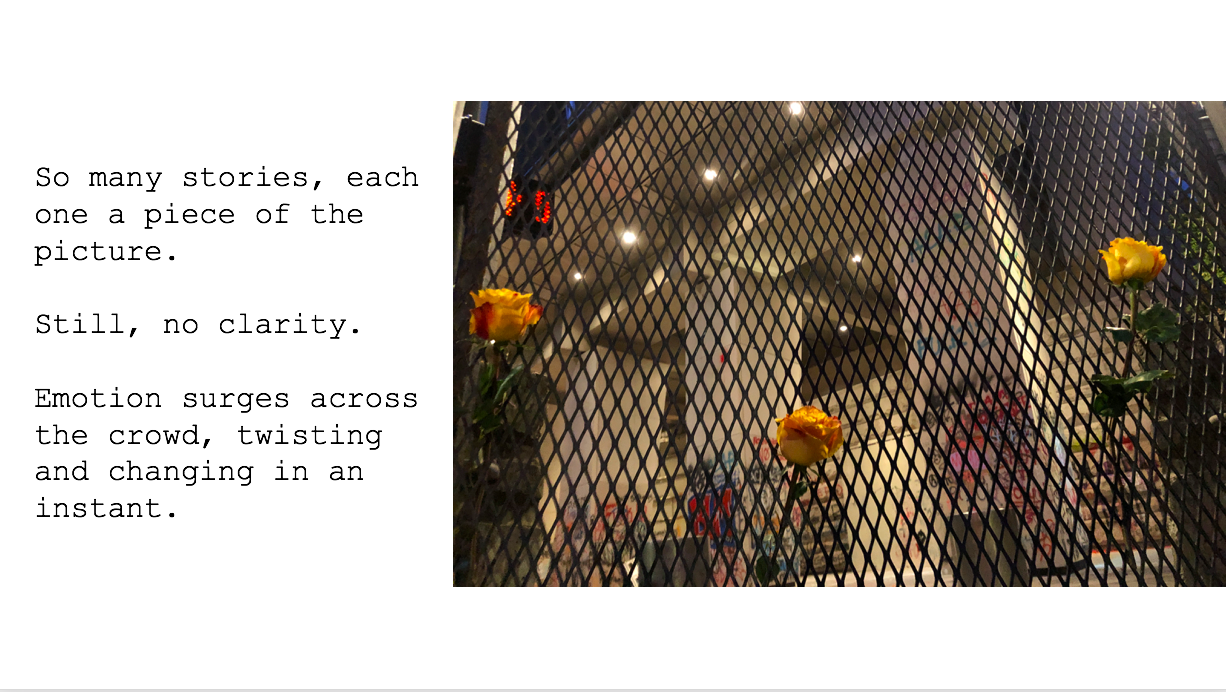

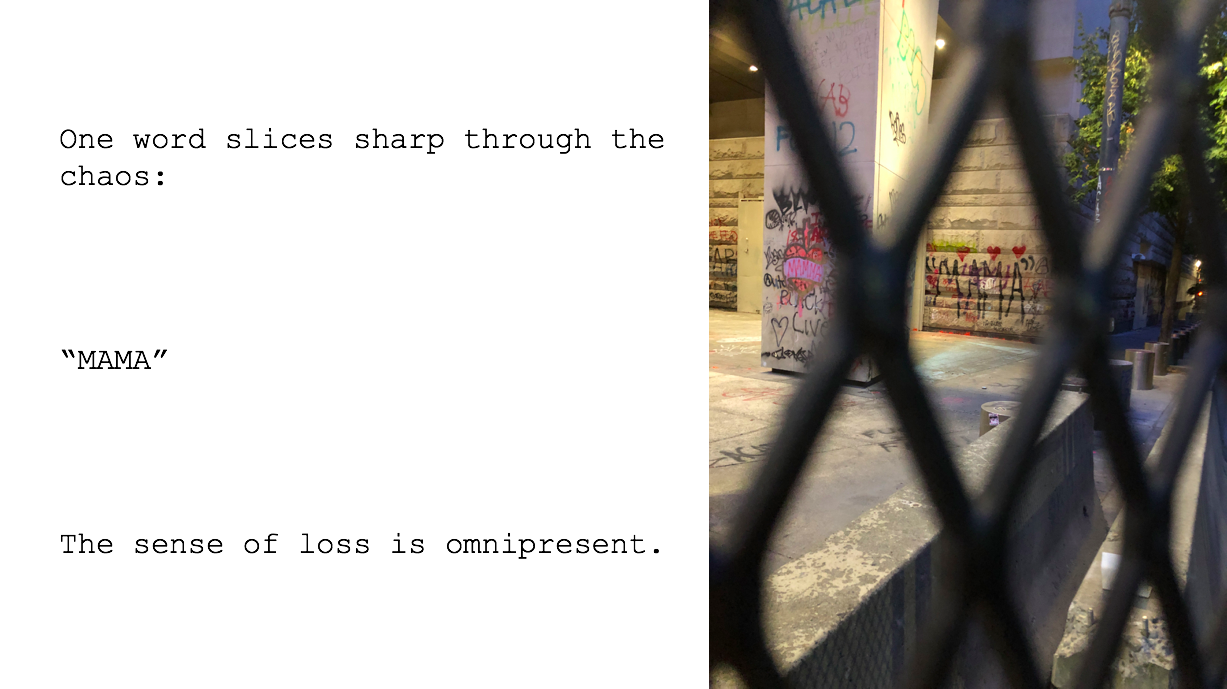

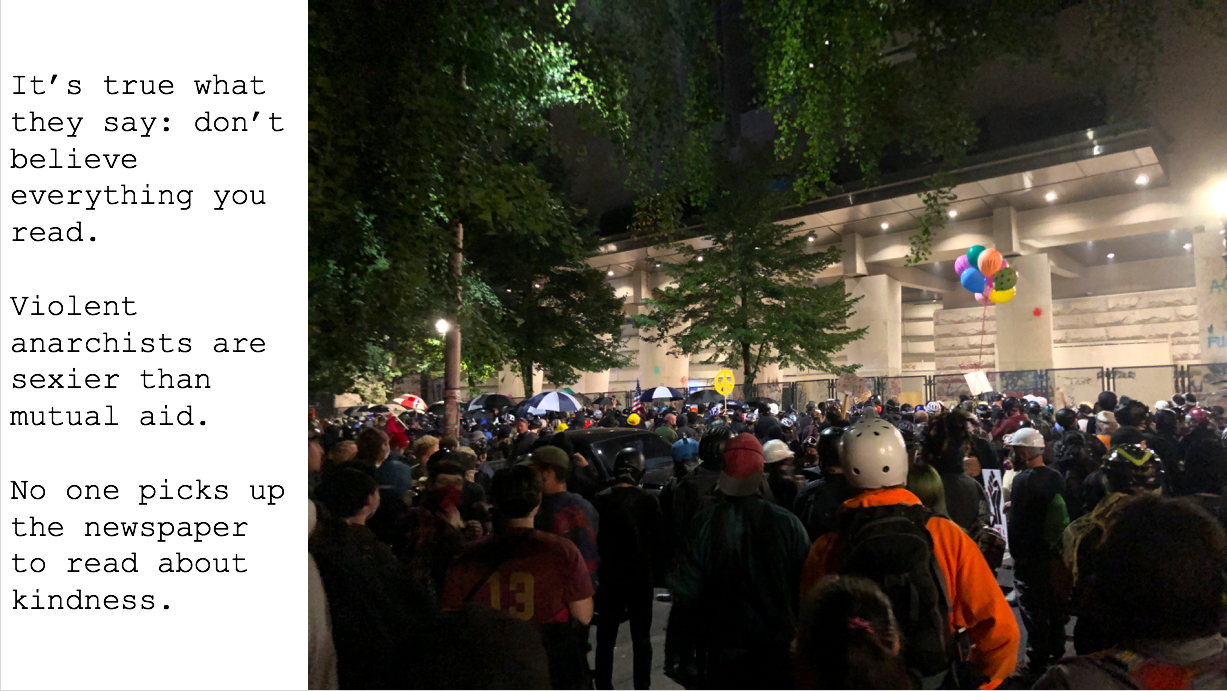

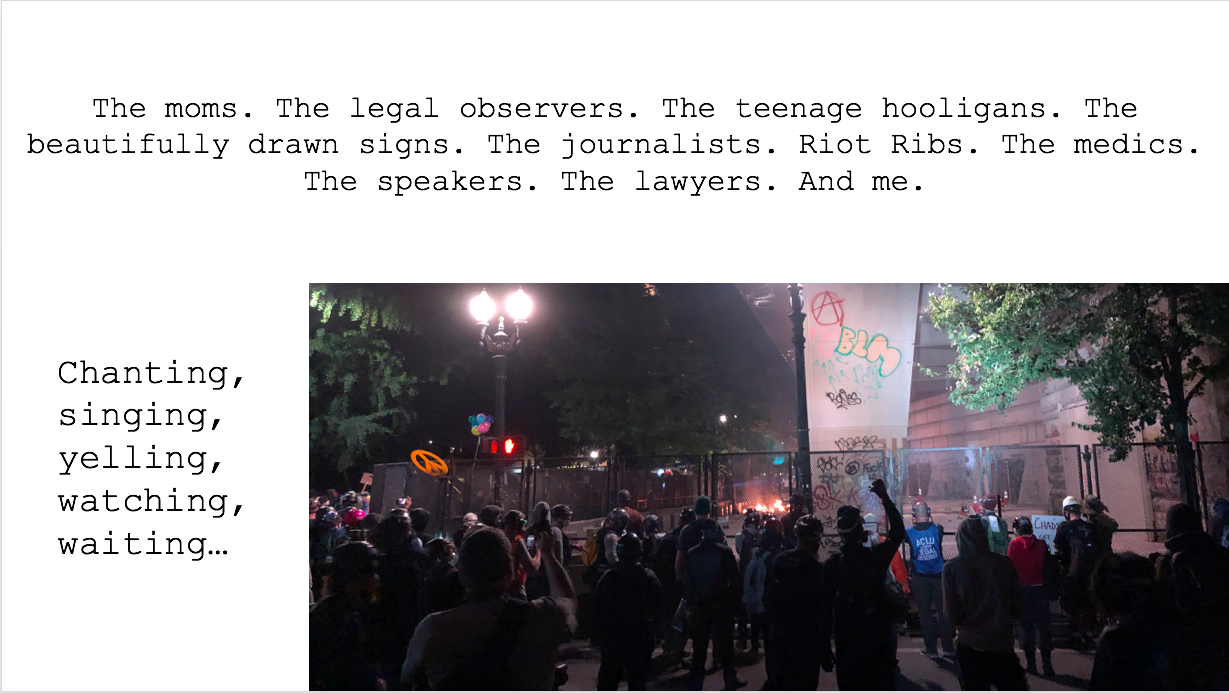

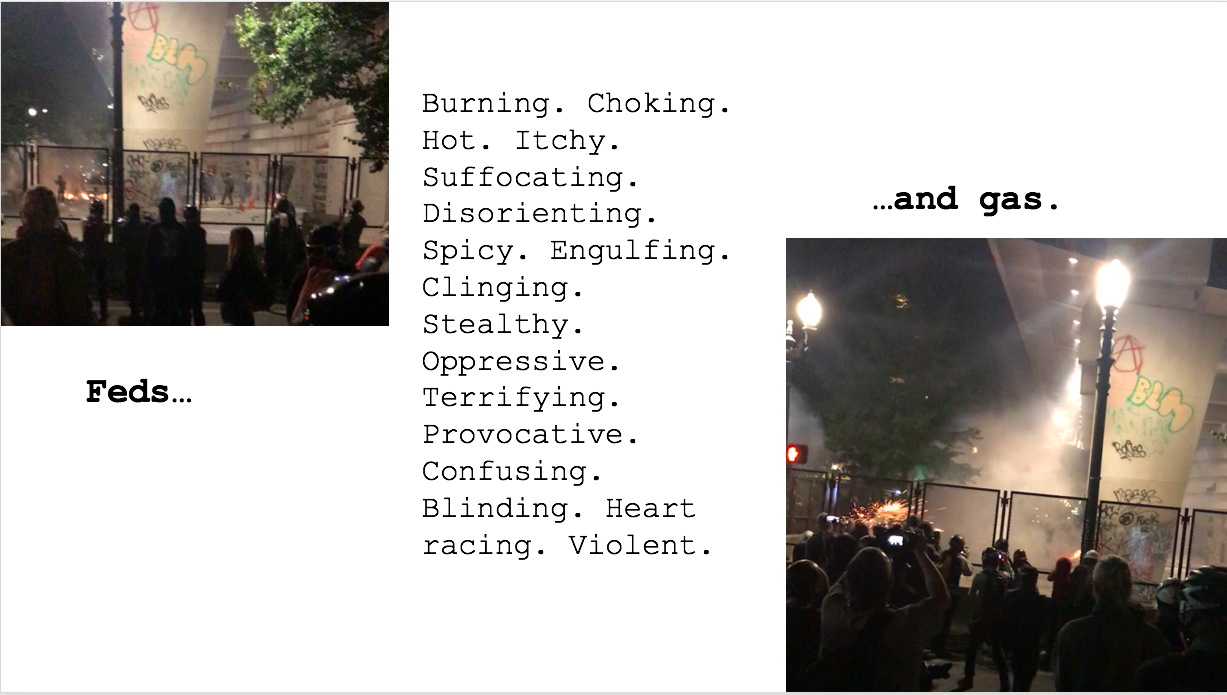

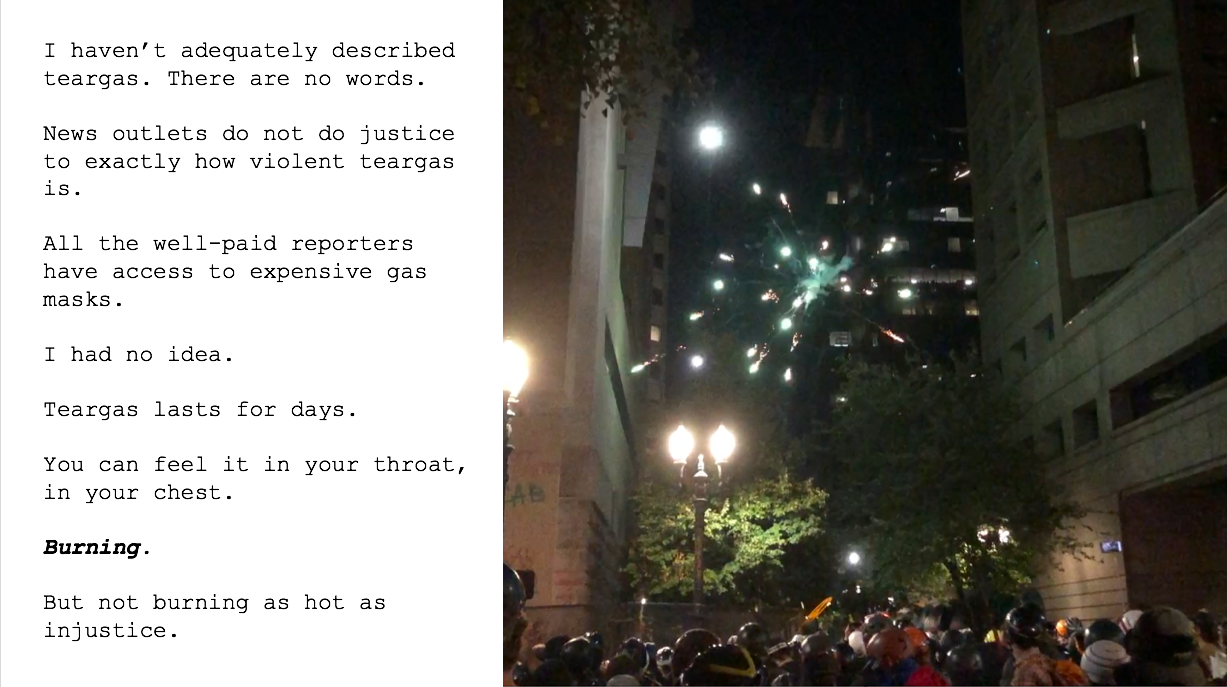

Protest Poetry

By Wrigley Kline

Loved Ones from Commissary

By Ali Marsh

Accumulated Adulthood

By Ali Marsh

poetic Justice

By Robert Johnson

What goes around, Or, A sewer runs through it

By Robert Johnson

Law & SOCIAL SCIENCE: Refereed Articles & Legal Notes

Section Editor: Brittany Ripper, J.D.

Defense of an Incarcerated Individual’s Right to Self-Preservation

By Cassandra Moore

ARTS: Essays, Stories, Images, & Poems

Section Editors: Robert Johnson & Benjamin Feder

The SHU

Tiffany Gilligan

Welcome to the SHU

Where I am the soul

Boxed like a new shoe

Worn down like an old sole

Concrete comfort

Designed for long term wear

Laces tied so tight

I’m gasping for air

Shoes on the outside- a sign of individuality

The SHU on the inside- a sign of abnormality

Of course, I know

All shoes must come with a price

But the price of this SHU

A human life?

Solidified Thoughts

Tiffany Gilligan

I know the pain of my nighttime brain

intrusive thoughts, irrational fears, invisible memories

not a sharp or searing pain

a slow burn

embers spreading

My nighttime brain is temperamental and often vengeful

using my imagination against me

sometimes it so graciously lets me sleep

other times, it pesters me like a two-year-old

asking “why?” to questions that don’t have answers

My nighttime brain has a personality of its own

personal to me

acting on its own

Convincing me of something I am not

I don’t know the pain of solitary

but I do know the pain of my nighttime brain

and I imagine solitary welcomes and encourages a nighttime brain

far beyond the dark of night

and well into the light of day

for much of the morning

and in the early evening

stealing minutes, blurring time

A nighttime brain in solitary?

a crime disguised as a punishment

Criminal Justice Class

Tiffany Gilligan

An academic thought experiment of sorts

speculate about consequences

to punish the punished

imprison the soul, heart, mind, or body?

take your pick

Solitary confinement?

The prison system chose them all

trapping souls, hearts, minds, and bodies

punishing the punished

by

starving the senses

Where is the sense in that?

cold consequences

lives lost

minds numbed

students seeking solutions

sitting in a safe classroom

studying sickening stories

scrutinizing senseless systems

sensitive scholars, striving to comprehend the

inexplicable

Feeding on the Hand

Tiffany Gilligan

Staring at the large, locked rusting door

Praying it will magically swing open

The thin food slot makes me salivate

Not for the processed prison porridge

But for a taste of fresh air

a human hand

a hand that feeds me the interaction I yearn for

I know this hand is the physical extension of the system

The system that's trapping me in here

I picture this hand around my neck

suffocating me

at least it's touching me

The hand serves to feed, my soul feeds on the hand

Solitary Seasoning

Tiffany Gilligan

The guard brings me my meal

jamming the food through the slot

and slamming it closed

The food on top brushes along the grimy, cold metal

caked and coated with dust and rust

Leaving a redolent residue

We call Solitary Seasoning!

Daughters of Thetis

Chandra Bozelko

For Thetis so loved her son

that she sunk him into the Styx to assure he would live forever.

No man could fell the warrior dipped in sacred water

-

But fluid mechanics

foiled her plan

shielding the flesh pinched in her fingers.

No grip so tight

is impenetrable.

-

An arrow aimed at his heel

undid him.

Would artisanal affronts have done the same

if trained on his insecurities

-

the way prison guards

sordid modern gods

focus on mine

and on my sisters

-

Labelling us

-

Bitch.

Dumb bitch.

Stank pussy bitch.

Whore.

Psycho.

Piece of shit.

Dirty ass.

Fat ass.

Dumb ass.

Crackhead.

Lowlife.

Scammer.

Thief.

Murderer.

-

We fantasize retorts, accuracy, a balanced battle

rather than target duty.

We see flaws that bleed beyond your badge.

We want us to become two Achilles

Each piercing the other’s heel.

-

But we can’t. At the gate

you stripped me of my quiver and

painted my powerlessness fluorescent pink

enabled language to unlock my soft spots and turn

modern prisons into ancient Greece.

-

Just another place where the gods are spiteful and cruel.

What happens at the intersection of race, disability, and the criminal justice system?

Wrigley Kline

This summer has seen an increase in activism surrounding the killing of Black people at the hands of police. One of the killings that saw a surge of activism was the killing of Elijah McClain. Elijah was killed in August of 2019 after someone called the police saying he was acting suspiciously, no doubt in part because he was wearing a ski mask on warm summer day. Elijah was wearing a ski mask because he was anemic, and anemia causes coldness throughout the body. The mask also helped to mitigate his social anxiety. Police thought that Elijah was resisting and they used force on him. EMTs injected Elijah with a large dose of ketamine, which contributed to a cardiac incident that left him comatose. He was taken off life support several days later (Lampen, 2020).

You have probably already heard this story. I hope you heard about what a kind person Elijah was. The diligent work of activists has led to the attorney general of Colorado opening a new investigation to see if there was any criminal wrongdoing. Most of the discussion about Elijah’s murder has taken place in the context of the Black Lives Matter movement, but there is another layer of intersectionality that must be considered: disability. While Elijah wasn’t diagnosed with a specific disability, it is important to remember that in our system of for-profit healthcare, diagnosis is a privilege.

The police made racist and ableist assumptions when they saw a Black man wearing a ski mask. Because of social anxiety, Elijah acted differently than the police expected him to (Lampen, 2020). The intersection of Elijah’s race and his needs led the police to murder him. If Elijah hadn’t needed to wear a ski mask, maybe the passerby would not have thought he was suspicious, or if Elijah was a white man in a ski mask, the passerby they may never have called the police. Once the police arrived, their biases against Black men combined with their expectations for how an average person behaves made them afraid of Elijah. This fear caused the police and EMTs to inject Elijah with a lethal dose of Ketamine to get him under control. There are many more stories of Black disability in the justice system that perhaps you haven’t heard of. Those stories paint a troubling picture of the way systemic failures harm vulnerable people.

Before I continue, I need to make it clear to you that I am a white autistic woman. This is not my story; this is not my lived experience. But I want to talk about these stories because they are not being heard. While there are countless think pieces and op-eds about the Black Lives Matter movement published in prestigious newspapers and magazines, none of them seem to touch on this particular intersection of identity, even though disabled Black indigenous people of color (BIPOC) people are particularly vulnerable. Black lives matter. Disabled people are not a burden. Black disabled lives are valuable.

One story that needs to be heard is Matthew Rushin’s story. Matthew is a Black autistic man with a traumatic brain injury. He was working and going to college until one rainy night in January of 2019 when he was involved in a car crash that severely injured another driver. Matthew’s parents maintain that the crash was an accident, while prosecutors say that the crash was a suicide attempt, based their (misinformed) interpretation of words Matthew stated at the accident scene (Coutu, 2020). Matthew signed a plea agreement without fully understanding what the plea meant, and was sentenced to 50 years, with a requirement to serve 10 years (Vargas, 2020).

In the wake of the murder of George Floyd, there has been an increase in attention to the injustices in Matthew Rushin’s case. A Change.org petition calling for Virginia governor Ralph Northam has been signed by over 200,00 people. One of the reasons that Matthew’s story has caused so much anger is that the evidence used by the prosecution demonstrates a clear misunderstanding of autism. Prosecutors argue that Matthew stated he was trying to kill himself, but when he exited his vehicle he was confronted by a bystander who angrily asked Matthew if he was trying to kill himself. Matthew repeated the phrase, a phenomenon known as echolalia (NC). Echolalia is the repetition of sounds or language, and it is a common autistic trait. Echolalia often helps children develop language skills, and it can also be brought out in stressful situations (such as after a car crash).

Experts have also debated Matthew’s medical state at the time of the crash. He appeared dazed and confused but tested negative for all intoxicants. Some people questioned if he had a seizure (Vance, 2020). He was not taken to a hospital after the crash. No matter Matthew’s medical condition at the time of the crash, one thing is clear: he has not been receiving proper medical attention while incarcerated. Matthew was transferred to a carceral facility away from his family and has not been given the medical attention his family has requested. Matthew has been experiencing headaches, dizziness, and periodic blindness, and has not been given an MRI (Tolley and Rushin, 2020).

Unfortunately, Matthew’s story is not unique. In the United Kingdom, Osime Brown, another Black autistic man, is facing deportation: deportation to a country he cannot remember. The British system has failed Osime throughout his life. He was not diagnosed with autism until he was 16, despite having many classic autistic traits. Around the time of his diagnosis, Osime was permanently expelled from school. After this, Osime was taken into the custody of social services, under unclear circumstances (Bulman, 2020).

The crime that has led to Osime’s likely deportation from the United Kingdom to Jamaica is another clear example of prosecutors’ misunderstanding of autism. When Osime was 15 years old he was involved with a group of teens who stole a phone from another young person. He was charged under the United Kingdom’s joint enterprise law, which allows multiple people to be charged for a single crime. The law has been criticized for its disproportionate use against Black people (Bowcott, 2016). Osime was with a group of other young people who exploited his autistic naivete and extreme willingness to comply with instructions. Prosecutors did not take this into account and the UK’s Home Office is also not taking his disability into account when they ordered his deportation. The Home Office is also disregarding Osime’s high support needs, healthcare needs, and frequent self-harm in prison (Dawson, 2020). Osime finished his five-year prison sentence this week, but the UK government still intends to deport him (Bulman, 2020). Going through with this deportation would demonstrate a clear misunderstanding of Osime’s situation.

Matthew and Osime are emblematic of the way the system criminalizes being Black and disabled. There are countless stories about being Black and disabled in the criminal justice system, but Matthew and Osime’s experiences overtly illustrate the problem with the system. Another reason it is crucial to discuss Matthew and Osime’s stories is that they are experiencing the full justice process. Many conversations about race and the justice system only focus on police killings, but for the majority of people being victimized by the justice system, that is not where their experience ends. There are many ways the system can fail those who our society is prejudiced against, and murder, while the starkest example, is only one way the system fails. When talking about justice, the conversation must include those behind bars.

It is important not to conflate systemic racial oppression with ableism. The two forces overlap to create a unique form of marginalization; that is the nature of intersectionality. The assumptions our society makes about the character of Black men combined with ignorance about the realities of being disabled has led police officers, prosecutors, judges, and jail staff to be complicit in the inhumane treatment of these young men.

So what do these stories tell us? Well, there’s an old adage, that you can learn a lot about a society based on how it treats its most vulnerable. Societies with carceral justice systems are failing Black people, disabled people, and those we deem ‘criminal’. We have desperately inadequate healthcare, a blatant disregard for the wellbeing of those who differ from the socially constructed norm, and a uniformly indifferent approach to infinitely complex people. Even people who refuse to empathize with Black disabled ‘criminals’ should be made uncomfortable by the fact that anyone in our society is treated this way.

My overall critique is with the way the United Kingdom and its former colonies conceptualize justice. I could have stuck to American examples of the justice system unjustly harming Black disabled people, but I didn’t, because the problem is bigger than that. The idea that punishment can right a wrong is a major oversimplification, and when this philosophy is implemented at a mass scale, vulnerable populations are hurt the most. It would take another entire essay to argue that punishment is not the way to achieve justice, and plenty of those essays have been written, so I will leave you with the reminder that this system is failing. These failures disproportionately penalize those who are different from the socially constructed norm — specifically people with differences those in power do not understand and often have come to fear. Black disabled people deserve better; all marginalized people deserve better: it’s time for change.

References

Bowcott, O. (2016, February 18). Joint enterprise law: What is it and why is it controversial? Retrieved October 05, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/law/2016/feb/18/joint-enterprise-law-what-why-controversial

Bulman, M. (2020, March 15). 'He will die out there': Severely autistic man facing deportation to Jamaica. Retrieved October 05, 2020, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/deport-autistic-jamaica-osime-brown-uk-home-office-a9400101.html

Bulman, M. (2020, October 07). More than 100,000 people call for deportation of severely autistic man to be halted. Retrieved October 08, 2020, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/deportation-autistic-man-jamaica-osime-brown-home-office-b802158.html

Coutu, P. (2020, June 15). Hundreds march in Virginia Beach to free former ODU student sentenced to 10 years for car crash. Retrieved October 05, 2020, from https://www.pilotonline.com/news/vp-nw-matthew-rushin-march-20200614-yla3fosnzrawjls6g7qhd6azni-story.html

Dawson, B. (2020, October 5). A Severely Autistic Man Faces 'Potentially Life-Threatening' Deportation. Retrieved October 05, 2020, from https://www.vice.com/en/article/g5p484/osime-brown-deportation-uk-jamaica-autism

Lampen, C. (2020, August 11). What We Know About the Killing of Elijah McClain. Retrieved October 05, 2020, from https://www.thecut.com/2020/08/the-killing-of-elijah-mcclain-everything-we-know.html

Tolley, B., & Rushin, L. (2020, October 05). What If You Were Matthew Rushin's Mother? Retrieved October 05, 2020, from https://themighty.com/2020/07/matthew-rushin-autistic-car-accident-arrest/

Vance, T. (2020, July 22). URGENT: Matthew Rushin is in Prison for Being Black and Autistic " NeuroClastic. Retrieved October 05, 2020, from https://neuroclastic.com/2020/06/09/urgent-matthew-rushin-is-in-prison-for-being-black-and-autistic/

Vargas, T. (2020, October 02). Perspective | A young black autistic man was sentenced to 50 years for a car crash. Tens of thousands of people are now calling for his freedom. Retrieved October 05, 2020, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/a-young-black-autistic-man-was-sentenced-to-50-years-for-a-car-crash-tens-of-thousands-of-people-are-now-calling-for-his-freedom/2020/06/24/fabeda1a-b640-11ea-a8da-693df3d7674a_story.html

Why Did I Stop Him?

Eliza Orlando-Milbauer

Why did I stop him from killing himself? What do you mean? That’s the job. My job is to keep them alive until execution day and I was doing just that. Once one of them gets riled up, they all get riled up. We have got to maintain order here. Nothing is more important. Look at the inmates on death row. We got murderers, rapists, serial murderers, serial rapists. I stand between you and them. You think these guys follow orders? You think these guys are rational? Easygoing? Suicide is a rule-break simple as that, and once you start relaxing on any of the rules, that’s when we lose control.

I follow the rules, let me tell you that. I follow the orders I am given, because I know what it means to do the right thing. To be a law abiding, respectful citizen. These guys on the row, they act like they are the only ones ever who have had a tough go of it, the only ones ever asked to follow some rules and do things they don’t like. I didn’t come from money, I didn’t come from picket fences and summer homes. Yet, every day, I wake up, I come here and I earn my living. It’s hard work but it's earned work. The men here, they cheat the system and they will keep cheating the system, until their last breath. It would be easier for me to have let him kill himself last night, just turned a blind eye, pretending there was no difference between his suicide and his execution. But it is not my choice when someone lives or dies. His victims did not get to choose when they died. He didn’t give them the choice. He doesn’t get to choose when he dies, what kind of justice would that be?

The state listened to what he had to say, they listened to what the experts had to say, they listened to what the families had to say, and they handed out justice. They said justice would be him dying yesterday at midnight when he did. He can’t avoid justice because he thinks he’s better than the system. And when the time came he got a lot more justice than his victims. We gave him a last meal, anything of his choosing. We let his family visit, let them say goodbye. We gave him the chance for final words and an audience to listen. Then, we anesthetized him, quietly, quickly, painlessly. A humane execution, more of a science than anything else. Maybe more than he deserved. But that it is not my job to determine. My job was to get him to justice day. I did my job, and I did it right. Hell, I wouldn't even let a condemned man die a few hours early.

The guys on death row have nothing to lose. We do. That is a dangerous game to be playing. They are in survival mode, and we are working for the weekend. We stand between them and maybe freedom, maybe death. It doesn’t matter. They aren’t thinking logically and we just want to make it through the day. Execution day is the worst. The air gets electric, everybody knows what’s going on. Make’s your hair stand on edge, just from the tension. It’s like the witching hour, dead men banging and hollering for a dead man, a ghost’s parade.

You all come in here and ask me why I did what I did; which system of ethics I relied upon, which philosophy drove my decision. That just is not how it works down here. I was a kid when I took this job, so naive, no idea what was coming. I came in all green, looking for a paycheck and to do some good for the country. Man, there is nothing good down here. When they try to kill themselves on the row, they don’t have many options. Luckily he tried to hang himself, but I have scraped too much brain matter off the floor of these cells to think this has anything to do with moral philosophy. We have the death penalty, and somebody has got to do it. My job was to strap down his right leg and let society do what it felt needed to be done. End of story.

A Woman in Prison Reflects on Selective Abuses of Police Authority

Erin George

Fluvanna Correctional Center

July 21, 2020

These are turbulent times as the nation grapples with the murder of George Floyd and other abuses of authority by police. Citizens of all ethnicities and ages flood the streets demanding change as a coward shivers in his government-subsidized bunker. I am not able to join the demonstrations because I'm in prison, but at least, I thought, I could share my own story about the police. Here it is.

The day I was arrested, my two older children were at school, so I'd spent the morning running errands with my youngest, Gio. We'd just had lunch at Applebee's, and she drowsed in her car seat in the back seat as we approached our home.

As we got closer to the house, I saw a cluster of people standing in my driveway: two men in suits whom I recognized as the detectives who had been investigating the death of my husband months before and a woman I'd never seen before. As my SUV pulled into the drive, they all stepped back to give me room.

The detectives watched me quietly as I unbuckled Gio from her seat, only approaching when I finally clutched her in my arms. Respectfully, even gently, they told me that I was being arrested for the murder of my husband. Did I have any questions, they asked. Who can we contact to take care of your children? The woman, they explained, was a social worker who would make sure that my Gio would be safe and my other two children met at the school bus that afternoon.

I was numb and handed Gio to the clearly kind and concerned woman after one last, desperate embrace. I was allowed to lock my car, and when Gio began to cry and reach for me, the detectives let me hold her again, to calm her and try to explain, as best I could to such a young child, that everything would be OK. I later learned that the social worker had taken Gio to a close friend's house and that all of my children were immediately surrounded by people who loved them.

After giving Gio back again, I was carefully handed into the detectives' car, brought to the police station, and booked.

There, then, is my experience with the police.

It doesn't sound familiar, does it? It's nothing like all of the other stories we've all heard, the stories of violence and heartbreak that so many have endured.

You can justifiably ask, why is my story so different? What made me so special? Did I have political clout or great wealth? Was I a celebrity? Or did the detectives arresting me have some doubts about my guilt? I did not and was not. And the cops most assuredly did not.

What I was was a middle class, suburban white woman, no one special except to my family and friends. That, it seems, was enough to ensure that I'd have no remarkable arrest experience to relate.

But when I hear other people's--black and brown people's--horrific stories of injustice and violence, I cannot use my own benign experience to dismiss those tragedies as aberrations, the acts of "a few bad apples" in the police ranks: the violence is too well-documented and widespread to dismiss.

No, my own story is only further proof of the poisonous open secret that taints our entire society: that there exists two parallel justice systems in America, one based on the ideals that give us the moral high ground as we preach to other countries for their human rights abuses, and a second that perpetuates those very same abuses we decry elsewhere.

What other explanation is there? How else could I, a woman accused (and eventually convicted) of murder, only feel the touch of a policeman as one chivalrously guided my head to avoid an unpleasant bump while being seated in his car while generations of black men, women, and even children have felt a knee on the neck, a taser's jolt, a bullet's deadly blaze, simply for being suspected of selling loose cigarettes, passing a phony twenty dollar bill, or playing with a toy in a park?

My absence of such a story is not specific to me. White people have cell phones, too, after all, and I'm sure that if in white neighborhoods white suspects were being murdered by cops on the flimsiest of excuses, there'd be footage everywhere.

When I think about my childhood, I can't remember a single instance of seeing a police car patrolling our neighborhood. In fact, the only time I ever saw a cop was when we had an assembly at school once about avoiding drugs. Nor did local police patrol the gated community where I eventually bought my own home. When I was arrested, I didn't know of a single person among my family or friends who had also been arrested, much less incarcerated. I'd certainly never had to receive a talk from my parents instructing me on how to avoid being murdered by the police.

I know how privileged I was. But I am no more responsible for that privilege than people of color are for their own circumstances. So how, in a country that brandishes its ideals like a club, can something so random as a circumstance of birth determine whether you will walk or be carried away from an encounter with the police? And how much longer can people like me ignore it?

Companion 1

Benjamin Feder

If the Kenosha shooting happened anywhere else in the world…

Wrigley Kline

If the Kenosha shooting happened anywhere else in the world, we would be calling it terrorism. This teen executed two people in the street. If he had done the same thing at a market in the Middle East and his social media was filled with posts idolizing jihadi martyrs instead of white supremacist content, he would quickly be labeled as a terrorist. Or, if he had traveled to Ukraine to be a foreign fighter and shot up a protest there, he would obviously be a terrorist. In the US, he is supposedly just a misguided kid. Here I should add an articulate sentence about American exceptionalism and how the stories we tell our children from a young age teach us to empathize with white male protagonists, no matter how morally corrupt, while simultaneously painting a wide variety of minority identities as dangerous, but I’m too drained to write that sentence.

In 2018 the Kenosha Sheriff gave a speech with eugenicist undertones:

"I'm to the point where I think society has to come to a threshold where there are some people that aren't worth saving… We need to build warehouses to put these people into it and lock them away for the rest of their lives. … Let's put them in jail. Let's stop them from, truly, at least some of these males, going out and getting 10 other women pregnant and having small children. Let's put them away. At some point, we have to stop being politically correct. I don't care what race, I don't care how old they are. If there's a threshold that they cross. These people have to be warehoused, no recreational time in the jails. We put them away for the rest of their lives so the rest of us can be better."

~ Kenosha County Sheriff David Beth, via The Hill

You may assume that Sheriff Beth was talking about a terrible serial killer, the stuff of dramatic true crime documentaries, but you would be wrong. He was talking about several teens who shoplifted and got in a car crash that resulted in minor injuries. Of course, all of the teens involved in the shoplifting incident were black. When a person in power says they don’t care about race, you know whatever comes next is probably going to be racist. I want to say, ‘I can’t believe that in 2020 we have sheriffs who believe in biological theories of crime,’ but to be honest, I’m not at all surprised.

I often find that people use the term “politically correct” as a synonym for basic human decency. I am not surprised that officers so casually shot Jacob Blake in the back when the head of their department has such a callous disregard for human life. If the Sheriff wants to warehouse, sterilize, and torture people (many human rights groups agree that not permitting exercise in confinement is torture), then murdering them is not a huge leap to make. I’m not in the mood to make historical analogies. It was obvious a long time ago that this police department needed intervention. Someone should have stepped in before Jacob Blake was shot. Our current situation is untenable, yet I don’t see a path forward for change.

Sources:

The Hill: “Kenosha sheriff after shoplifting case in 2018: Some people 'aren't worth saving'” By Marina Pitofsky. https://thehill.com/blogs/blog-briefing-room/news/514119-kenosha-sheriff-after-shoplifting-case-in-2018-some-people

The Washington Post: “Before a fatal shooting, teenage Kenosha suspect idolized the police” By Teo Armus, Mark Berman and Griff Witte. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/08/27/kyle-rittenhouse-kenosha-shooting-protests/

Protest Poetry

Wrigley Kline

Loved Ones from Commissary

By Ali Marsh

My voice carries but your

names are too heavy. So,

I remain silent.

To speak of you is to remember and

that’s something I won’t do.

But,

at night, I pretend bags of Cheetos are bags

of time I reach into to pull out cheese puff

versions of the people I knew

Each one a loved one I refuse to

chew; to chew is to taste and to taste is to know

and to know is to remember–

I swallow and

forget.

The angles of their faces cut and bruise

my throat on their way to stomach safety,

But,

I do not blame you.

This is why, you see, I must remain

silent.

Accumulated Adulthood

Ali Marsh

The tide is lower than usual today and

the crocodiles are already hungry

The house’s creaks woke me up earlier than I’d like, but

I found solace in knowing I was capable of beating the sun,

even if only by chance

With a win in my back pocket and nothing to do, I allowed

myself to relish in the snooze button–once, twice, three times–

until two hours had passed and I reluctantly gave into existence

Stood up with dizziness and a fear of normalcy, I cracked

my neck and waited for pre-ordered smoothies to be

placed on my doorstep with the overpriced-ness and

flavor I’d grown accustomed to

Sipping on calories, dread and chunks of date, I watched

beadlets of June drip down my arm onto the blue velvet couch '

I sunk deeper into each day

Absorbent, the couch became stained with a shared anger

for the world’s failure to warn us: Summer was just a season

Disgusted, I climbed out of reality into my padded skull shelter in

search for something new, but nothing ever is and I never seem to

learn, brought back by desperation, delusion and the knowledge

that truth is just what you beat yourself into believing

Finding nothing but the familiarity that causes divorce, I began

my daily sift through the list of all the things I could do today

but wouldn’t.

Poetic Justice

Robert Johnson

Build prisons

Not day-care

Lock ‘em up

What do we care?

Hire cops, not counselors

Staff courts, not clinics

Wage warfare

Not welfare

Invest in felons

Ripen ‘em like melons

Eat ‘em raw, then

Ask for more

More poverty

More crime

More men in prison

More fear in the street

More ex-cons among us

Poetic justice

What goes around, Or,

A sewer runs through it

Robert Johnson

gray, gloomy stone wall

hulking, soaring

silver, shiny metal wire

sharp, gleaming

bare, barred steel cage

brutal, brooding

tarnished, stained tin toilet

stench seeping

out

flush

whoosh

discharge

They all

get out

They all

come back

If only

In a box

Bringing

a little bit of prison

with them

Law & SOCIAL SCIENCE: Refereed Articles & Legal Notes

Section Editor: Brittany Ripper, J.D.

Defense of an Incarcerated Individual’s Right to Self-Preservation

Cassandra Moore

Introduction

Many prisons are often deemed a violent and dangerous place, where incarcerated individuals and prison staff face the ever-present threat of violent victimization - including assault, and even homicide. Jails and prisons enclose impulsive and often angry individuals in tight quarters regardless of their mental state and previous crimes, creating a powder keg for potential violence. Violent predators are sometimes placed in cells with vulnerable incarcerated people who are offered little protection by staff. Given these realities, a large portion incarcerated people live with some degree of fear and fear of victimization. To stay sane and alive, incarcerated individuals are forced to develop coping mechanisms and survival tactics in order to proceed in their now fear-induced lives.

Hobbes proposed that the life of man is “nasty, brutish, and short,” drawing parallels to an incarcerated individual’s life and circumstance behind prison walls.[i] Many prisons could essentially be in a perpetual state of war, as Hobbes suggests is the state of nature. In such a state, each individual is responsible for protecting oneself against harm and the state cannot restrict him/her from doing so, since that is an inherent right endowed to all. In prison, incarcerated individuals must utilize various means of self-defense in order to present a bravado of power and control to provide a layer of protection against potential violence. Perception is integral to maintaining security against possible threats of violence. The way in which incarcerated individuals are viewed by others is essentially their first means of defense against those who wish to do them harm. Thus, incarcerated individuals who are seemingly less inclined to violence may adopt a more aggressive or intimidating persona in order to cope with the stressors and potentially survive their dangerous environment. Given the increased levels of violence and victimization within prison, the state cannot justifiably restrict an incarcerated individual’s right of self-defense by punishing them when they attempt to protect their self. Regardless of whether an individual is incarcerated, there are fundamental and innate rights that cannot be restrained – most paramount being the right to self-defense and self-preservation.

Fear and Victimization

Incarcerated individuals are often overcome by intense feelings of fear, as they often face constant risk of victimization beyond prison walls. A chapter in Hard Time which focused on violence in prison noted that in some prisons “violence [is] a fact of daily prison life.”[ii] In an environment meant to control and confine you, the violence that persists within prisons is therefore inescapable. In comparison to the copious dangers incarcerated individuals are confronted with, there are little means of protection. A case study of Canadian incarcerated individuals regarding threats noted that all 56 incarcerated individuals interviewed “reported feeling insecure” either regarding their wellbeing or what they may succumb to during their time in prison.[iii] These feelings of insecurity are prompted by lack of security and protection from staff, coupled with direct and indirect threats from other incarcerated individuals. Upon entering prison, incarcerated individuals are thrown into an environment where their mental and physical health are no longer guaranteed. There are constant threats that induce feelings of anxiety and stress for incarcerated individuals with little avenues to address or cope with such disruptions to their mental state. The previously discussed study insists that “risk perceptions have a spatial-temporal dimension, perceived threat is ever-present and, thus, needs to be negotiated on a permanent basis,” which undeniably affects an incarcerated individual’s mental ability to handle stressors in the prison environment.[iv]

Additionally, different incarcerated individuals face varied levels of perceived and real threats. As previously discussed, a sizeable number of incarcerated people face the perpetual threat of violence, which ultimately instills an overwhelming fear of victimization. However, depending on an incarcerated individual’s circumstance, they face varied levels of victimization depending on their ability to protect their self and whether they are made to be a target behind the prison walls. There are a multitude of factors that put particular incarcerated individuals at greater risk for potential victimization. A study on assault in Ohio and Kentucky prisons noted that younger incarcerated individuals, incarcerated individuals with less institutional protection, and those with “higher security classifications were more likely to offend and to be victimized.”[v] Though, it should be noted a significant enough portion of incarcerated individuals face potential victimization, and there is evidence to prove that these categories of incarcerated individuals are at an increased threat of potential violence. This increased threat of creating fear and its endurace it increases feelings of anxiety for incarcerated individuals. In fact, in Hard Time, through accounts from incarcerated individuals and prison staff, it is suggested that “fear was at the epicenter of many prisoners’ problems with serious misbehavior.”[vi]

Prison presents individuals with threats of violence unlike unparallel by most other environments and some incarcerated individuals face greater volumes of threats. Such feelings of fear and victimization paired with social and administrative regulations that present incarcerated individuals with a variety of additional hurdles simply to protect one’s self. There is a dichotomy between an incarcerated individual’s fear of victimization and their ability to protect themselves. Throughout their prison sentence, incarcerated individuals must regularly grapple with threats of violence or acts of intimidation. They have no ability to control their surrounding environment and thus have a dimishinshed ability to calm feelings of fear and anxiety that accompany such threats. According to rules and regulations in many prisons, incarcerated individuals cannot defend themselves against any acts of violence. This ensures their abuse and guarantees a life, within prison, of constant fear.

Stressors

The need for survival is an innate human right that cannot be morally be restricted. However, behind prison walls, incarcerated individuals cannot react violently in any scenario - even if their lives are threatened. In addition to overwhelming threats of violence, incarcerated individuals face copious stressors that make survival more difficult to guarantee in prison. There are social and institutional restrictions that prevent incarcerated individuals from taking action against potential threats. The aforementioned study of Canadian prisons notes that the relationship between administrative regulations and the “prisoner’s code” places incarcerated individuals at a significant disadvantage when addressing potential threats.[vii] Incarcerated individuals must maintain balance in their relationships with other prisoners and the staff, a feat which presents them with an abundance of internal and external challenges. These can include feelings of anxiety and, unfortunately, an increased likelihood of victimization.

With regards to prison staff, incarcerated individuals must follow correctional officers’ directions and maintain a stable relationship in order to avoid administrative repercussions. However, with other incarcerated individuals, prisoners must simoltaneoulsy adopt an intimidating persona as a means of ensuring their own protection. These positions often exist in opposing planes and clash with one another, making an incarcerated individual’s life unpredictable and dangerous. Evidence examined in Hard Time suggests that this dichotomy causes incarcerated individuals to be “easily provoked to violence by the stresses of prison life.”[viii] A significant number of incarcerated individuals face a constant battle between maintaining social and institutional order in prison and their own survival. In addition, the fear of victimization and the requirement to abide by spoken and unspoken rules present incarcerated individuals with copious difficulties, making life in prison a seemingly impossible maze to navigate.

Coping Mechanisms

Along with the restriction of individual liberties, some incarcerated individuals are given little access to avenues for cognitive or rehabilitative therapy, which would provide incarcerated individuals an avenue for coping with the increased fear and anxiety they face. Instead, incarcerated individuals are responsible for developing means of coping. Unfortunately, the only resource provided to them is that which they bring to their cell on their own accord – their persona or bravado. The persona incarcerated individuals project may be their only means of coping and survival. Incarcerated individuals must “continuously try to create a sense of stability, predictability, and security in an overall unsafe environment” and their means of doing so often revolve around acts of intimidation and violence.[ix] According to the study of Canadian prisons, incarcerated individuals adopt certain “’fronts’ in an effort to fit into the prison community and avoid exploitation.”[x] Such fronts are integral to maintain a sense of security and safety since incarcerated individuals can only rely upon how they are perceived by others as protection. The perception of danger and power provides incarcerated individuals with a necessary shield against possible victimization from other incarcerated individuals. Violent individuals often prey on the vulnerable in prison. Therefore, incarcerated individuals cannot risk appearing weak.

Hard Time echoes this claim and asserts “the code dictates that individuals maintain a tough or violent demeanor in order to secure respect from others, and if disrespected, they must respond forcefully.”[xi]A study on prison violence in particular found that “acts of violence that occur in prisons, however, are rarely strategic. They are generally reactive—an impulsive response to an acute situation.”[xii] Incarcerated individuals must continually adapt to their environment, which constantly dictates their action or reaction. The ways in which they chose to cope with their surroundings is determined by their environment and the unspoken rules that govern it. Essentially, to survive, incarcerated individuals must present a domineering exterior that other incarcerated individuals would be deterred to act against or abuse. Canadian prisoners note that this bravado is a form of “safekeeping” and further explain that “using violence or ‘fighting back’ is the most effective strategy to demonstrate one’s physical prowess and strength.”[xiii]

Additionally, security levels in prison can determine how incarcerated individuals chose to react to situations. According to administrative control theory, studies show that incarcerated individuals are less inclined to use violence or react in volatile ways in institutions where there are higher levels of control.[xiv] This means that they do not feel as responsible for their own safety when protection is provided by other actors. When little protection is provided by institutional factors and prison staff, incarcerated individuals must then rely on their self in order to cope with the stressors of prison and mitigate threats of violence from other prisoners. Anxiety and fear overwhelm incarcerated individuals throughout their sentences. So, they must adapt to their surroundings and adopt tactics and strategies as a means of survival. Thus, preemptive acts of violence should therefore be viewed as self-defense as they are often an individual’s desperate attempt for self-preservation.

Conclusion

In life threatening situations, individuals adopt a fight or flight mentality. Although circumstances differ greatly in free society compared to prison, incarcerated individuals generally adopt the same mentality when their lives are threatened. The fight or flight reaction coincides heavily with the nature versus nurture debate. Are our actions predetermined by our biology, or, rather, are they shaped by the environment and surroundings that we are born into? Answering such question is integral to determining whether individuals have a predisposition towards violent behavior or if instead, the behavior is learned. Biology alone cannot effectively explain if an individual will behave violently. Rather, the environment and the ways in which people must adapt to their environment determine whether violent action or use of force is necessary for survival.

The only ways in which prisoners can effectively protect themselves is to deter others from harming them in the first place. An article published in the Law & Order journal insists that “intellect alone” is the only attribute that allows for survival.[xv] In this instance, incarcerated individuals’ intellect and experience in prison lead them to believe that preemptive violence is the only effective mean of self-defense. Moreover, an article from the University of Chicago Law Review contends that “The ubiquity of violence […] illustrate[s] the importance of protection from violence in the prison context, and thus the importance of the right to self-defense.”[xvi] The restriction of certain liberties is synonymous with imprisonment; however, the right to self-defense can never justly be restricted, regardless of one’s previous crimes. In a specific case regarding a prisoner’s right to self-defense, the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit concluded that imprisonment restricts one’s right to self-defense if there are “legitimate penological goals.”[xvii] However, the dissenting opinion in that case form Judge Ripple noted that penological goals are not in fact enough to holistically strip an individual of their innate right of self-defense. The judge goes further and insists there is significant absurdity in the fact that state, when restricting an individual’s liberty, can go further and “punish that individual for attempting to stay alive” when the state has failed in its responsibility to protect all incarcerated individuals.[xviii] Essentially when the state fails, incarcerated individual’s should not be held responsible for acting in means of self-defense with the intent of fighting to stay alive.

Every individual is endowed with the right to self-preservation, and in the context of prison, the need to be able to take action in order to guarantee one’s survival and preservation is integral. Threat of violence and abuse are pervasive within prison walls and a vast majority of incarcerated individuals are overcome with perpetual feelings of anxiety and fear that ignite their fight or flight instincts. In order to survive and defend themselves, incarcerated individuals adapt to their surrounding by adopting intimidating characteristics that will deter other violent incarcerated individuals from taking violent action against them. In the most extreme of circumstances, incarcerated individuals may be driven to engage in preemptive acts of violence in order to survive in a dangerous, threatening environment. These acts should be considered acts self-defense with the purpose of self-preservation and thus cannot justifiably be restricted by the state.

[i] Hobbes, Leviathan

[ii] Johnson, R. (2001). The Public Culture of Prison: Violence. Hard Time, pg 110.

[iii] Maier, K. H., & Ricciardelli, R. (2019). The prisoner’s dilemma: How male prisoners experience and respond to penal threat while incarcerated. Punishment & Society, 21(2), 231-250 pg 234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474518757091

[iv] Maier, K. H., & Ricciardelli, R. (2019). The prisoner’s dilemma: How male prisoners experience and respond to penal threat while incarcerated. Punishment & Society, 21(2), 231-250 pg 241. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474518757091

[v] Wooldredge, J., PhD., & Steiner, B., PhD. (2013). Violent victimization among state prison incarcerated individuals. Violence and Victims, 28(3), 531-51. Pg. 546. doi:http://dx.doi.org.proxyau.wrlc.org/10.1891/0886-6708.11-00141

[vi] Johnson, R. (2001). Prison Violence. Hard Time, pg 16.

[vii] Maier, K. H., & Ricciardelli, R. (2019). The prisoner’s dilemma: How male prisoners experience and respond to penal threat while incarcerated. Punishment & Society, 21(2), 231-250 pg 233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474518757091

[viii] Johnson, R. (2001). Prison Violence. Hard Time, pg 14.

[ix] Maier, K. H., & Ricciardelli, R. (2019). The prisoner’s dilemma: How male prisoners experience and respond to penal threat while incarcerated. Punishment & Society, 21(2), 231-250 pg 246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474518757091

[x] Maier, K. H., & Ricciardelli, R. (2019). The prisoner’s dilemma: How male prisoners experience and respond to penal threat while incarcerated. Punishment & Society, 21(2), 231-250 pg 232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474518757091

[xi] Johnson, R. (2001). Prison Violence. Hard Time, pg 16.

[xii] Noll, T. (2015). Prison Violence. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 59(4), 335–336, pg. 336. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X15573246

[xiii] Maier, K. H., & Ricciardelli, R. (2019). The prisoner’s dilemma: How male prisoners experience and respond to penal threat while incarcerated. Punishment & Society, 21(2), 231-250 pg 242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474518757091

[xiv] Wooldredge, J., PhD., & Steiner, B., PhD. (2013). Violent victimization among state prison incarcerated individuals. Violence and Victims, 28(3), 531-51. Pg. 546. doi:http://dx.doi.org.proxyau.wrlc.org/10.1891/0886-6708.11-00141

[xv] Oldham, S. (2010). Nature versus nurture. Law & Order, 58(3), 34. Retrieved from http://proxyau.wrlc.org/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.proxyau.wrlc.org/docview/1034979564?accountid=8285

[xvi] Kaye, A. (1996). Dangerous Places: The Right to Self-Defense in Prison and Prison Conditions Jurisprudence. The University of Chicago Law Review, 63(2), 693-726, pg 724. doi:10.2307/1600239

[xvii] Prison Legal News. (1994). No Right to Self-Defense in Prison. Prison Legal News. https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/1994/jul/15/no-right-to-self-defense-in-prison/

[xviii] Prison Legal News. (1994). No Right to Self-Defense in Prison. Prison Legal News. https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/1994/jul/15/no-right-to-self-defense-in-prison/

Author Biographies

Erin George is serving a life sentence in Virginia. She is the author of poetry (Origami Heart) and prose (see Tacenda Literary Magazine archives) published by BleakHouse Publishing.

Wrigley Kline is an undergraduate student at American University pursuing a degree in Justice, Law, and Criminology with a concentration in Terrorism Studies. She is dedicated to intersectional activism with an emphasis on disability acceptance. Her passion for social justice has led her to focus her studies on issues of identity-based terrorism. She hopes to go on to do research in this field.

Ali Marsh is a recent graduate of American University where she earned a degree in Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies with a minor in Justice. As an undergrad, Ali studied abroad in both Madrid and a studio arts college in Florence, Italy, where she completed intensive creative writing, photography, performance art, and sculpture courses. Both experiences were heavily documented and turned into self-published books consisting of film photos, reflections, and poems. Upon her return to the states, Ali interned as a writer for Ms Magazine, writing about social issues from a feminist lens. In addition to her love for writing and art, Ali's work in social activism has led her to be featured in Vice, Time Magazine, the New York Times, as well as numerous other publications.

Cassandra Moore is a recent graduate from American University with a Bachelor of Arts in Law and Society. While at American, Cassandra worked at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, the DC Pretrial Services Agency, the DC Office of Police Complaints, and The Death Penalty Information Center. She possesses a concern for incarcerated individual's rights, carceral reform, and is interested the study of the death penalty and its practices within the United States. Before graduation, she received the Catheryn Seckler-Hudson Award for Student Achievement from American University in May of 2020. Cassandra will be presenting her work on the self-defense rights of incarcerated individuals at the virtual Criminology Consortium in November of 2020 and at the International Congress of Law and Mental Health in Lyon, France in 2021.

Eliza Orlando-Milbauer is an undergraduate student at American University pursuing a degree in Political Science with a concentration in public policy and a minor in Education Studies. While at American she has served as a reviewer for Clocks and Clouds, the university's research journal. She is also a recipient of the Amos Perlmutter Endowment Scholarship for academic success in the field of comparative politics. Through her studies she has become focused on the role of educational justice in facilitating decarceration in the United States.

Chandra Bozelko is a syndicated columnist. She writes the weekly column “The Outlaw” for Gannett Media. She is also the author of Up the River: An Anthology, a book of poetry published by Bleakhouse Press.

Tiffany Gilligan is a graduate from American University with a Bachelor of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies: CLEG (Communications, Law, Economics, and Government). During her studies, she became particularly interested in her criminal justice courses that focused on incarceration. As an intern at the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, she corresponded with incarcerated individuals to offer personalized support and resources. Hearing their stories shined a light on the human toll and experience of the criminal justice system. Deeply concerned with this human toll, she enjoys using poetry to express her thoughts and feelings.

Editor Biographies

Robert Johnson is a professor of Justice, Law, and Society at American University and a widely published author of fiction and nonfiction dealing with crime and punishment. His short story, "The Practice of Killing," won the Wild Violet Fiction Contest in 2003. Several of his works have been adapted for the stage. His best known work of social science, Death Work: A Study of the Modern Execution Process, won the Outstanding Book Award of the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences.

Benjamin Feder is an American University student currently pursuing a master’s degree in Art History, with a focus on the Italian Renaissance. His experiences as both an artist and a student of art history are what initially compelled him to start a career in the art industry. Benjamin has worked in museums and galleries in both New York City and Washington D.C, and is currently working in collections management. As an artist, Benjamin’s favorite medium is clay, though he often includes mixed media into his sculptures.

Brittany Ripper, J.D., is a doctoral student in Justice, Law and Criminology at American University and a legal consultant for BleakHouse Publishing.